|

Subtitle: War, Peace and the

Course of History - Alfred Knopf, NY., 2002, 919 pgs., index, bibliography,

extensive notes

|

|

| |

Reviewer Comment

This is one of the most important books on the history of our age, how the

'State' began, its principle role - that of conducting war, how it developed,

how it was legitimized by contemporary writers, its constitution and strategy,

the constitution of the society of states, what is happening to it now and some

thoughts on where it is going. The author combines excellent descriptions of

the ephocal wars, including their tactics and technologies, that transformed it

with much less well known discussion and analysis of the theories created to

legitimize it. It is a perfect companion to Dr. Bobbitt's later book Terror

and Consent, in which he focuses on the role of terror during each of

the epochs described here. Both books are essential studies for understanding

current events and future possibilities.

So what is this 'State' and when and how was it created and for what purpose?

The "State' is an abstract concept that was developed during the

Renaissance to replace the concept of the 'Great Chain of Being" which had

served as the source of legitimacy for rulers, justified their power to

establish law, and defined the relative places and roles of the members of

society, during the European Middle Ages. It stands outside of and above

society and rulers. It developed when rulers (both individuals and republican

governments) were still prevented from marshaling all the resources of their

polities by medieval custom and law from raising sufficient enough to wage war.

The 'State' is a child of war - that is the wieldier of violence, both

domestically via its constitution and externally via its strategy.

In the list of references below I include the histories in the "Rise of

Modern Europe" series that contain more details on the periods of

transformation which Dr. Bobbitt discusses here.

|

|

| |

Forward By Sir Michael

Howard

"There have been many studies of the development of warfare even more of

the history of international relations, while those on international and

constitutional law are literally innumerable. But I know of none that has dealt

with all three of these together, analyzed their interactions throughout

European history and used that analysis to describe the world in which we live

and the manner in which it is likely to develop.

Bobbitt goes back to an older and bleaker tradition: that associated with the

name of Niccolo Machiavelli..."

|

|

| |

Prologue The End of the

Long War and the Transformation of the Modern State

In the prologue Professor Bobbitt writes a summary of the entire book while

describing how it is organized.

"This book is about the modern state - how it came into being, how it has

developed, and in what directions we can expect it to change. Epochal wars,

those great coalitional conflicts that often extend over decades, have been

critical to the birth and development of the State, and therefore much of this

book is concerned with the history of warfare. Equally determinative of the

State has been its legal order, and so this is a book about law, especially

constitutional and international law as these subjects relate to statecraft.

This book, however, is neither a history of war nor a work of jurisprudence.

Rather it is principally concerned with the relationship between

strategy, and the legal order as this relationship has shaped and transformed

the modern state and the society composed of these states. A new form of the

State - the market state - is emerging from this relationship in much the same

way that earlier forms since the fifteenth century have emerged as a

consequence of war."

"As a result of the Long War, the State is being transformed and this

transformation is constitutional in nature, by which I mean we will change our

views as to the basic reason d'etre of the State the legitimating

purpose that animates the State and sets the terms of the State's strategic

endeavors."

"The nation-state's model of statecraft links the sovereignty of a state

to its territorial borders."

"Because the international order of nation-states is constructed on the

foundation of this model of state sovereignty, developments that cast doubt on

that sovereignty call the entire system into question."

"Five such developments do so:

(1) the recognition of human rights as norms that require adherence within all

states, regardless of their internal laws:

(2) the widespread deployment of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass

destruction that render the defense of state borders ineffectual for protection

of the society within;

(3) the proliferation of global and transnational threats that transcend state

borders, such as those that damage the environment, or threaten states through

migration, population expansion, disease, or famine;

(4) the growth of a world economic regime that ignores borders in the movement

of capital investment to a degree that effectively curtails states in the

management of their economic affairs;

(5) the creation of a global communications network that penetrates borders

electronically and threatens national languages, customs, and cultures."

The Relationship between Military Innovation and Change in the Constitutional

Order

"A revolution in miliary affairs brought forth the modern state by

requiring an organized system of finance and administration in order for

societies to defend themselves."

But if we see, on the contrary, that each of the important revolutions in

military affairs enabled a political revolution in the fundamental

constitutional order of the State, then we will be able not only to better

frame the scholarly debate but also to appreciate that the death of the

nation-state by no means presages the end of the State."

The Relationship between the Constitutional order and the International Order

"Every society has a constitution. Every society does not require a state,

But every society has a constitution because to be a society is to be

constituted in some particular way."

"Each great peace conference that ended an epochal war wrote a

constitution for the society of states"

Yet, all constitutions also carry within themselves the seeds of future

conflict."

How to Understand the Emerging World order of Market-states

"This book offers and answer: that we are at one of the half dozen turning

points that have fundamentally changed the way societies are organized for

governance."

"The modern state came into existence when it proved necessary to organize

a constitutional order that could wage war more effectively that the feudal and

mercantile orders it replaced."

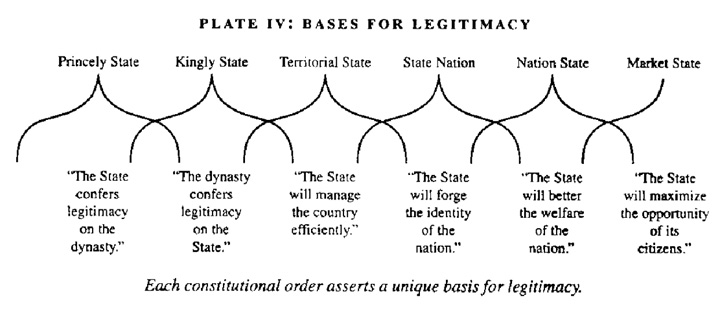

"Each new form of the State is distinguished by its unique basis for

legitimacy - the historical claim it makes that entitles the State to

power."

"The emergence of the market-state will produce conflict in every society

as the old ways of the superseded nation-state fall away."

The Future of the State

"A new constitutional order - the market-state- is about to emerge."

"Whatever course is decided upon will be both constitutional and strategic

in nature because these are the two faces of the modern state - the face the

state turns toward its own citizens, and the face it turns toward the outside

world of its competitors and collaborators."

The Structure of this Book

"The Shield of Achilles treats the relationship between strategy

and law. The first part deals with the State, and the second takes up the

society of states; whereas the first is largely devoted to war and its

interplay with the constitutional order of the State, the second concentrates

on peace settlements and their structuring of the international order."

"At the beginning of each of the six parts of this combined work, a

general thesis is set forth as a kind of overture to the narrative argument

that is then provided."

Book I of this work, focuses on the individual state; it is divided into three

parts, which correspond to three general arguments."

Part I "The Long War of the Nation State" argues that the war that

began in 1914 did not end until 1990."

Part II provides "A Brief History of the Modern State and the

Constitutional Order" beginning with the origin of the State in Italy at

the end of the fifteenth century and ending with the events that began the Long

War. These chapters assert the thesis that epochal wars have brought about

profound changes in the constitutional order of states through a process of

innovation and mimicry as some states are compelled to innovate, strategically

and constitutionally, in order to survive, and as other states copy these

innovations when they prove decisive in resolving the epochal conflict of an

era."

Part III of Book I "The Historic Consequences of the Long War" argues

that the Long War of the twentieth century was another such epochal war, and

that it has brought about the emergence of a new form of the State, the

market-state."

While Book I treats of the individual state, Book II, "States of

Peace," deals with the subject of the society of states. The state system

is a formal entity that is composed of states alone and defined by their formal

treaties and agreements. The society of states, on the other hand, is composed

of the formal and informal customs, rules, practices, and habits of states and

encompasses many entities - like the Red Cross and CNN - that are not states at

all."

Part I of Book II, "The Society of Nation-States", deals with the

society of states in which we currently live."

Part II of Book II "A Brief History of the Society of States and the

International Order" revisits the historic conflicts that have given the

modern state its shape and which were the subject of Part II of Book I.

"In Book II, however, the perspective has changed. Here I am less

concerned with epochal wars than I am with the peace agreements that ended

those wars. Part II makes the claim that the society of modern states has had a

series of constitutions, and that these constitutions were the outcome of the

great peace congresses that ended epochal wars."

"Part III "The Society of Market-States" depicts the future of

the society of states." Professor Bobbitt then describes the reason he

titled this book "Shield of Achilles" and discusses Hephaestus's

mirror and the shield he created for Achilles.

He comments, "war is a product as well as shaper of

culture."

|

|

|

Book I: State of War

|

|

|

Introduction: Law,

Strategy, and History

"Law, Strategy, History - these ancient ideas whose interrelationship was

perhaps far clearer to the ancients than it is to us, for we are inclined to

treat these subjects as separate modern disciplines."

"War is won and international law changes..." "Or a war is lost,

with the consequence that a new constitutional structure is imposed..."

"Thus does strategy change law - and we call it history." or

"Law changes strategy, and this too we call history." or

"History itself brings new elements into play - .... - an empire falls and

with its strategic collapse die also its laws."

"We scarcely see that the perception of cause and effect itself - history

- is the distinctive element in the ceaseless, restless dynamic by means of

which strategy and law live out their necessary relationship to each

other."

"History, strategy, and law make possible legitimate governing

institutions."

"The State exists by virtue of its purposes, and among these are a drive

for survival and freedom of action, which is strategy; for authority and

legitimacy, which is law; for identity, which is history."

"There is no state without strategy, law and history, and, to complicate

matters, these three are not merely interrelated elements, they are elements

each composed at least partly of the others."

"The legal and strategic choices a society confronts are often only

recombinations of choices confronted and resolved in the past, now remade in a

present condition of necessity and uncertainty. Law cannot come into being

until the state achieves a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence,

Similarly, a society must have a single legitimate government for its strategic

designs to be laid; otherwise, the distinction between war and civil war

collapses, and strategy degenerates into banditry."

"Today, all major states confront the apparently bewildering task of

determining a new set of rules for the use of military force."

"The reason the traditional strategic calculus no longer functions is that

it depends on certain assumptions about the relationship between the State and

its objectives that the end of this long conflict has cast into doubt."

Professor Bobbitt writes that the major states no longer face the danger of

serious 'state-centered threats against which they can organize the kind of

defenses used in the past. but rather "The parliamentary state manifests

vulnerabilities that arise from a weakening of its own legitimacy."

He also comments on several widespread preconceptions that are now wrong. Among

these is that wars are started by aggressors. NO, he writes, wars come about

when defenders decide to resist.. "Rather, it is the state against whom

the aggression has been mounted, typically, that makes the move to war."

Another misconception is that wars arise due to miscalculation. A third

preconception arrises from presentism. - it is that "future states of

affairs must be evaluated in comparison with the present, rather than with the

unknowable future. In other words it is a mistake to evaluate a choice between

different options on the basis of what the choices would result in now. Rather,

one must evaluate the choices in terms of what the result of each selection

would be in the future.

The State is future oriented.

"It asks; will the state be better or worse off, in the future, if in the

present the state resorts to force to get its way?"

Professor Bobbitt then examines several current theories - deterrence,

compellance, and reassurance. He describes the origin of each and some of the

major authors. He also comments on several other books about the 'end of the

nation-state' and notes that they confuse this end with the end of the state

itself, which he disputes.

|

|

| |

Part I: The Long War of

the Nation - State

"Thesis: The war that began in 1914 will come to be seen as having lasted

until 1990."

|

|

| |

Chapter 1 - Thucydides

and the Epochal War

Professor Bobbitt starts out with Thucydides and the epochal Peloponnesian War,

then the Thirty Years' War. This is a brief 3 pages to set the scene.

|

|

| |

Chapter 2 - The Struggle

Begun: Fascism, Communism, Parliamentarianism, 1914-1919

All the wars from WWI to Cold War were part of one war over one issue.

"The Long war ..... was fought to determine what kind of state would

supersede the imperial states of Europe that emerged in the nineteenth century

after the end of the wars of the French Revolution..."

"The Long War was fought to determine which of three new constitutional

forms would replace that system: parliamentary democracy, communism, or

fascism."

"As we shall see in Part I, the legitimacy of the constitutional order we

call the nation-state depended upon its claim to better the well-being of the

nation."

Professor Bobbitt then proceeds to lengthy discussion of the content and

purposes of Fascism, (which he sees originating in essence with Bismarck). And

he credits Bismarck as one of the founders of the 'nation-state' itself

"the first European nation-state". He then discusses Communism which

seized power in Russia from the weak, new parliamentary government. It

radically changed the 'boundary between state and society' as virtually all

citizens became employes of the state.

|

|

| |

Chapter 3 - The Struggle

Continued: 1919-1945

"The relation between law and strategy, between the inner and the outer

faces of the State, is maintained by history - the account given of the

stewardship of the State."

Professor Bobbitt continues his narrative history with analysis of the

development of Fascism in Germany (and Italy) and Communism in Russia (plus

something also about Japan).

|

|

| |

Chapter 4 - The Struggle

Ended: 1945-1990

"The Long War now continued because it had not truly been ended. " He

discusses the Cold War at length including the Korean War, and, briefly, the

war in VietNam. He dates the end of the Long War "to November 1990 when

the thirty-four members of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe

met at Paris and signed an agreement providing for parliamentary institutions

in all the participating states". - the Charter of Paris. But this is not

the end of either the State nor of war. So, he asks, "what are the

strategic consequences of that peace?' "What will the new world look

like?"

|

|

| |

Part II: A Brief History

of the Modern State and it's Constitutional Orders

"Thesis: The interplay between strategic and constitutional innovation

changes the constitutional order of the state."

This is the section I find most interesting as excellent analysis of military

history

|

|

| |

Chapter 5 - Strategy and

Constitutional Order

Professor Bobbitt discusses in detail the several concepts about a 'military

revolution' first advanced by Michael Roberts in 1955. This was accepted by Sir

George Clark in 1958. It was then criticized by Geoffrey Parker, and then in a

different argument by Jeremy Black and even more by David Parrott. Professor

Bobbitt describes all these theories and concludes they were all partially

right but wrong in their basic conception that there would be one such

revolution (each example favored by its author). He writes that, "In the

chapters that follow, I will trace developments in strategy, from roughly the

end of the fifteenth century onward and relate these developments to changes in

the constitutional structures of the states of Europe." The issues on

which these authors based their ideas are minor. His conception is much deeper

and widespread. He continues,

"I propose, in the brief historical narrative that follows, to treat the

relationship between state formation and strategic change as that of a

field, as contrasted with those causal relations that are usually

characterized along a line."

|

|

| |

Chapter 6 - From Princes

to Princely States: 1494-1648

The "fall" of Rome created a new society with 'two parallel

structures- the Universal Church and the fragmented feudal system. "The

legal relations of these two entities were in principle separate."

"The defining legal characteristic of medieval society was its horizontal

nature, reflected across these two pervasive dimensions of ecclesiastical and

feudal power."

"Medieval society, however, was not divided into separate states, with

each prince a sovereign within his own territory, ruling hierarchically all

within that territory and no persons our territories remaining outside the

domain of some prince."

Professor Bobbitt gives and excellent description of the characteristics of

medieval society - its culture and political structure. He does not, however,

mention the underlying ideological basis of legitimacy in medieval society -

the 'Great Chain of Being'- the concept that God was at the top of this chain

and every person from emperor, pope, and king down to the lowest peasant was an

integral link in this chain. It was the collapse of this ideological source of

legitimacy and resulting vacuum that necessitated the creation of the abstract

concept of 'State' which Bobbitt then describes so well.

He notes, "the universal scope of the Christian community imposed

restraints on a prince's reasons for going to war." And I add serious

fiscal restraints as well.

"the princes of this period were not territorial in the sense of having a

fixed settlement and identification with that locality and its people..."

Princely States

Professor Bobbitt writes 15 pages of excellent detailed discussion of the

transition from princes to princely states including military technological

changes, political and economic changes and philosophical changes. He writes

that "This change was begun by the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 by

the Ottoman Turks. One does not often see this mentioned instead of French King

Charles VIII invasion of Italy in 1494, which Bobbitt lists second.

"Faced with such a strategic challenge (from artillery) Italian cities

could no longer simply rely on their high walls and fortified towns to protect

them."

"Thus, the modern state originated in the transition from the rule of

princes to that of princely states that necessity wrought on the Italian

peninsula at the end of the fifteenth century." Now, Bobbitt by 'prince'

and 'princely' does not limit the subject to literal princes but includes the

oligarchical and semi-democratic Italian city republics as well.

Bobbitt correctly notes the abstract conceptual nature of this new 'state'.

Prior governments and societies had no similar 'state' "the State is never

a 'thing' it has no 'legal personality' in past history.

He stresses about the previous eras:

"The State was always an irreducible community of human beings and never

characterized as an abstraction with certain legal attributes apart from the

society itself."

"The modern state, however, is an entity quite detachable from the society

that it governs as well as from the leaders who exercise power."

"All the significant legal characteristics of the State - legitimacy,

personality, continuity, integrity, and most importantly , sovereignty - date

from the moment at which these human traits, the constituents of human

identity, were transposed to the State itself."

There is much more in this chapter.

|

|

| |

Chapter 7 - From Kingly

States to Territorial States: 1648-1776

"From early in the sixteenth century until the middle of the seventeenth

two conflicts intertwined: the religious struggle that began with the

reformation and which; provoked horrific civil wars throughout Europe: and the

efforts of the Hapsburg dynasty to establish a true imperial realm in

Europe."

"These two interacting dramas culminated in the Peace of Westphalia in

1648, which ratified the role of the kingly state as the dominant legitimate

form of government in western Europe."

The Kingly States

In a compact 48 pages Bobbitt describes not only the character of the kingly

state and its rise and fall, but also the advent of the territorial state and

the significant differences between these two forms.

"The princely state in Italy had been developed by families who wished to

re-enforce their legitimacy to govern, and who required a more efficient means

of marshaling wealth in order to defend their claims by means of innovation -

fundamentally, the objectification of the state - and united this with dynastic

legitimacy."

"The strategic innovations of ever more expensive fortress design and

complex infantry fire crushed those constitutional forms that could not adapt

in order to exploit those innovations: first princely states, with their modest

revenue bases; then the discontinuous Hapsburg empire of princely states that

risked decisive battles in so many theaters that it was bled dry by the new,

more dynamic and lethal warfare."

"The chief advantage of the kingly state over the princely states it

dominated was sheer scale. Yet this advantage was not enjoyed by the Hapsburg

empire, which assembled a vast collection of princely states into a single

constitutional unit. It is important to see how, despite enormous wealth and

experienced forces, who were, as at Nordlingen, capable of devastating

victories, the Hapsburg imperial constitutional form was nevertheless

vulnerable to the escalating possibilities of violence posed by the revolution

in tactics."

"The sheer quantitative advantage that imperial and kingly forms shared

should not blind us to the constitutional qualitative difference between the

kingly state and the princely state."

But it was more than a revolution in tactics. Babbitt discusses the ideas of

Machiavelli, Bodin and Hobbes in the transition of theory from princely to

kingly state. He describes the efforts of Cardinal Richelieu to use the

'epochal' Thirty Years' War to complete the victory of the kingly state. But he

writes that it was Gustavus Adolphus who "more than other leaders used the

potentiality of the kingly state to exploit the military revolution begun by

gunpowder." "(Gustavus) realized that constitutional as well as

strategic reform was necessary."

"Whereas for the princely state the great leap is from the prince as

person to the prince plus an administrative structure - the prince and the Sate

- the transformation to the kingly state (the state already having been

objectified) reverses this move and makes the monarch the apotheosis of the

State".

"Princely states persisted in Italy and Germany because of powerful

competing cities in both places and owing to the presence of the papal states

in the former and irreconcilable religious division in the latter. These

thwarted the consolidation necessary for the creation of a kingly state in both

places."

"To put it differently: the princely state severed the person of the

prince from his bureaucratic and military structure, thereby creating a state

with attributes hitherto reserved to a human being; the kingly state reunites,

these two elements, monarch and state, and makes of the king the State itself:

(I am the state)".

"But the kingly state did not truly triumph as a stable and powerful

entity until constitutional centralization became a reality". "The

victory of the kingly state was accompanied by the broad introduction of

rationalism into European thought".

"Six institutional structures typified the kingly state; a standing army

(or navy),... a centralized bureaucracy; a regularized statewide system of

taxation, permanent diplomatic representation abroad; systematic state policies

to promote economic wealth and commerce; the placement of the king as the head

of the church."

But these were different from the conditions of the coming 'territorial state'.

Bobbitt describes the evolution subsequent to Peace of Westphalia of the now

supreme kingly state and the already beginning territorial state (such as

Netherlands - United Provinces of the Dutch was the first).

"The territorial state had special concerns that contrasted with those of

the kingly state. Whereas a kingly state was organized around a person, the

territorial state was defined by its contiguity and therefore fretted

constantly about its borders."

Bobbitt continues with a lengthy history of the kingly state (especially

France) and then of its conflict in the War of the Spanish Succession with the

new territorial states to which it ultimately succumbed at the Treaty of

Utrecht.

"The territorial state was characterized by a shift from the monarch as

embodiment of sovereignty to the monarch as minister of

sovereignty."

|

|

| |

Chapter 8 - From

State-Nations to Nation-States: 1776-1914

In another lengthy chapter Professor Bobbitt traces the continued development

of the state nation out of the territorial state and then its shift to the

nation-state. Again, he notes that at a given time some states might be, for

instance, still kingly while the majority were now territorial but leading

states were already becoming state nations. In fact some virtually leaped from

the rear to the front in the process of change. He points out that nations such

as France that remained 'kingly states' and didn't shift to the territorial

basis eventually lost the support of critical interest groups and were

destroyed in a direct change to the state-nation form. At the same time, these

states were then the first to become state-nations - France - and the rest were

then forced to follow along.

"What is a "state-nation," this curious phrase that seems no

more than a typographer's inversion of the familiar term in political science?

A state-nation is a state that mobilizes a nation - a national, ethnocultural

group - to act on behalf of the State. It can thus call on the revenues of all

society, and on the human talent of all persons. But such a state does not

exist to serve or take direction from the nation, as does a nation-state.

"

"By contrast the nation-state, a later phenomenon, creates a state in

order to benefit the nation it governs. "

Professor Bobbitt narrates and describes in detail the course of the Wars of

the French Revolution and Napoleon to show how the strength of the new

state-nation defeated the opposing territorial states and how these eventually

were forced to change their constitutions as well. Except that Germany and

Italy were so broken by religious and political divisions that they could not

convert at that time. As in the preceding chapters, the historical summary of

the wars is closely tied to the constitutional changes.

"But only when each of Napoleon's victim states had become persuaded that

it must change in order to save itself, did a society come into being that can

properly be called a society of state-nations."

"It is important to understand precisely what strategic innovations

Napoleon relied upon, and then to briefly chronicle his experience with them.

That will lead us to an understanding of the state-nation form he

created."

"And how it differed from the state-nation model created by Washington,

Hamilton and Madison."

An interesting conclusion Bobbitt reaches is that but for Napoleon's full scale

revolutionary strategy France more likely would have adapted from its

kingly-state form to the territorial-state form of its opponents, joining their

society rather than supplanting it. He explains: "And this speculation is

important for our wider study, because it suggests that a revolution in

military affairs is not sufficient, without further human agency, to bring a

new constitutional order into being."

In this chapter Bobbitt continues to describe the evolution of the State in the

19th century from state-nation to nation-state. His exposition begins with a

detailed analysis of the Congress of Vienna and the objectives and rolls of the

principal participants. In this he expounds a vital role for history.

"Every change in the constitutional arrangements of the State will have

strategic consequences and also the other way around, so that innovation in

either sphere will be reflected in the degree of legitimacy achieved by the

Sate, because legitimation is the reason for which a constitution exists, for

which the State makes war."

"Because history provides the way in which legitimation is conferred on

the State, history is the manifestation of the interactions of law and strategy

as history affords the means by which the State's objectives are rationalized.

History determines the basis for legitimacy. "

"Every era asks, "What is the State supposed to be doing?" The

answer to this question provides us with an indication of the grounds of the

State's legitimacy, for only when we know the purpose of the State can we say

whether it is succeeding. The nation-state is supposed to be doing something

unique in the history of the modern state: maintaining, nurturing, and

improving the conditions of its citizens."

"The transition from state-nation to the nation-state brought a change in

constitutional procedures."

|

|

| |

Chapter 9 - The Study of

the Modern State

"Open any textbook on constitutional law and you will find discussions of

the regulation of commerce and the power of taxation, religious and racial

accommodation, class and wealth conflicts, labor turmoil, and free speech, but

little or nothing on war". "Open any textbook on war and you will

find chapters on strategy, the causes of wars, limited war, nuclear weapons,

even the ethics of war, but nothing on the constitutions of societies that make

war - nothing, that is, on what people are fighting to protect, to assart, to

aggrandize".

"The state has two primary functions: to distribute questions

appropriately among the various allocation methods internal to the society, and

the determining what sorts of problems will be decided by asserting its

territorial and temporal jurisdictions vis-a-vis other states. These two tasks

are, respectively the work of constitutional law and strategy". "In

the preceding chapters it has been argued that there is a mutually affecting

relationship; between strategy and constitutional law such that some strategic

challenges are of so great a magnitude that, rather than merely requiring more

taxes, or more bureaucrats, or longer periods of war service, they encourage

and even demand constitutional adaptations: and that some constitutional

changes are of such magnitude that they enable and sometimes require strategic

innovation".

"Over the long run, it is the constitutional order of the State that tends

to confer military advantage by achieving cohesion, continuity, and, above all,

legitimacy for its strategic operations".

|

|

| |

Part III: The Historical

Consequences of the Long War

"Thesis: The Market State is Superseding the Nation-State as a Consequence

of the End of the Long War".

|

|

| |

Chapter 10 - The

Market-State

"Different constitutional orders are responsive to different demands for

legitimacy. Legitimating characteristics, such as dynastic rights, that are

sufficient for one constitutional order are inadequate for another".

The Crisis of the Nation State"

"As we saw in the historical narratives of Part II, the nation-state is a

relatively recent structure. Indeed, the modern State itself is of fairly

recent vintage in the life of civilized mankind, dating as it does from roughly

the end of the fifteenth century".

Dr. Bobbitt describes the crisis and its causes. Fundamentally they lie in the

"nature of the Long War and the strategic innovations by which that was

was won by the liberal democracies". He notes that each of the forms of

state described above inherited responsibilities and legitimizing

characteristics from its predecessors and added new ones. The strategic

innovations of the Long War "make it increasingly difficult for the

nation-state to fulfill its responsibilities".

"The new constitutional order that will supersede the nation-state will be

one that copes better with these new demands of legitimation , by redefining

the fundamental compact on which the assumption of legitimate power is

based".

"Three strategic innovations won the Long War: nuclear weapons,

international communications, and the technology of rapid mathematical

computation". "Each has wrought a dramatic change in the military,

cultural, and economic challenges that face the nation-state. In each of these

spheres, the nation-state faces ever increasing difficulty in maintaining the

credibility of its claim to provide public goods for the nation".

Security:

"The State exists to master violence: it came into being in order to

establish a monopoly on domestic violence, which is a necessary condition for

law, and to protect its jurisdiction from foreign violence".

Professor Bobbitt explains how and why the innovations of the Long War have

created conditions that reduce the capacity of the State to perform those

fundamental tasks.

Welfare:

Modern communications helped create the nation-state, were critical in waging

the Long War and now create the problems for the nation-state.

"The price these states were compelled to pay is the world market that is

no longer structured along national lines but rather in a way that is

transnational and thus in many ways operates independently of states". For

example: "Approximately four trillion dollars - a figure greater than the

entire annual GDP of the United States - is traded every day in currency

markets".

He describes other examples including some related to military vulnerabilities.

Culture:

" The third promise of the nation-state was that it would protect the

cultural integrity of the nation". "Here too the strategic

innovations of the Long War played a transformative role".

One outcome: "We will inevitably get a multicultural state when the

nation-state loses its legitimacy as the provider and guarantor of

equality".

Again, he continues with much more detail.

The Emergence of the Market-State:

Under this heading he explains why this is happening.

|

|

| |

Chapter 11 - Strategic

Choices

"The end of the Long War has also brought an end to the usefulness of the

strategic paradigm that structures so much of American policy during the more

than three score and ten years of U.S. involvement in the larger world, from

the reversal of his own isolationist policies by President Woodrow Wilson in

1917, to the proclamation of the Wilsonian "New World Order' by President

George Bush in 1990".

|

|

| |

Chapter 12 - Strategy and

the Market-State

Market-States: Mercantile, Entrepreneurial, Managerial

In this chapter the author describes his concept on how the nation-state will

change into a market-state and the three versions of the latter that will

compete for dominance.

"The fundamental choice for every market-state is whether to be (1) a

mercantile state - i.e. one that endeavors to improve its relative

position vis-a-vis all other states by competitive means, or (2) an

entrepreneurial state, one that attempts to improve its absolute

position while mitigating the competitive values of the market through

cooperative means, or (3) a managerial market-state one that tries to maximize

its position both absolutely and relatively by regional formal means .

This choice will have both constitutional and strategic implications". In

this 49 pages Professor Bobbitt concentrates a huge amount of ideas.

|

|

| |

Chapter 13 - The Wars of

the Market-State: Conclusion to Book I

"The Long War was an epochal war. Such wars are distinguished from other

types not simply by their duration - which often spans lengthy periods of

armistice - but mainly by their constitutional significance". "Let me

reiterate that the reasons epochal wars are begun are no different from those

of any wars: they arise from clashing claims to power, from competing

ideologies and religions, insistent ambition, the gamble for greater wealth,

sympathy for kinsmen or hostility to foreigners, and so on".

"The reason epochal wars achieve, in retrospect, an historic importance is

because however they may arise, they challenge and ultimately change the basic

structure of the State, which is, after all, a war-making institution".

"Because the very nature of the State is at stake in epochal wars, the

consequence of such wars is the transformation of the State itself to cope with

the Strategic innovations that determine the outcome of the conflict".

"Legitimacy is what unites the problems of strategy and law at the heart

of epochal war just as history supplies the answers to those problems".

"The State is born in violence: only when it has achieved a legitimate

monopoly on violence can it promulgate law: only when it is free of the

coercive violence of other states can it pursue strategy".

"In the preceding chapters I have argued that the constitutional order of

the State is undergoing a dramatic change". "This change is taking

place all across the society of states". "The market-state manifests

itself in three forms vis-a-vis the larger society of states: the mercantile,

managerial, and the entrepreneurial state". "The great powers will

repeatedly face five questions regarding the use of force in the twenty-first

century, and none of them are usefully characterized in the zero-sum,

conflictual way of strategic warfare. These questions are whether to intervene,

when to do so, with what allies, with what military and nonmilitary tools, and

for what goals".

Dr. Bobbitt writes more on this issue, the central one facing us today. He

includes quotations from Presidents Bush and Clinton who apparently recognized

that the change in the world economic-political structure requires change in

governments. The change is to recognize that the new form of a 'State' will be

a variation of the 'market-state'.

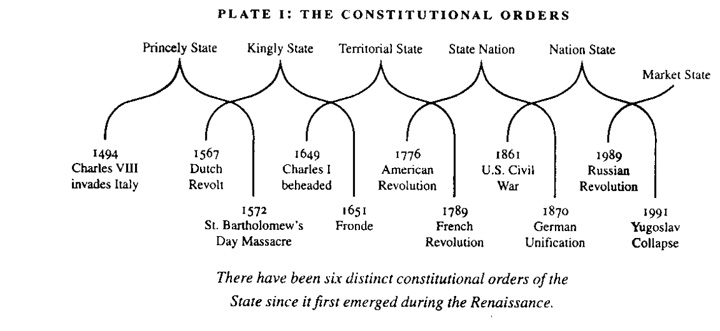

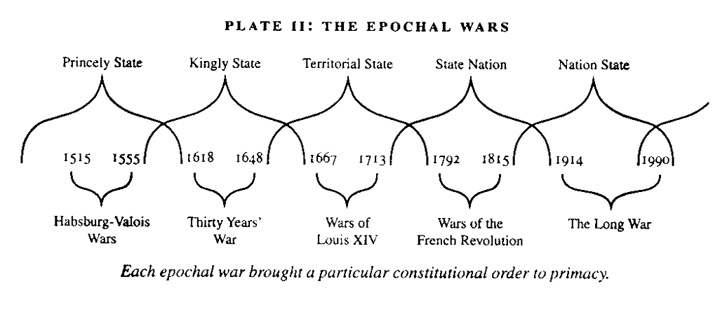

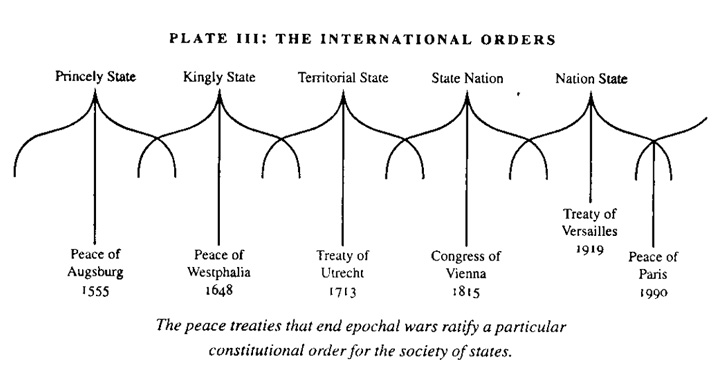

The following are five graphical representations of the six successive

constitutional conventions of the international society of states.

|

|

| |

Plate I - The Consitutional

Orders

There have been six distinct constitutional orders of the State since it first

emerged during the Renaissance

|

|

| |

Plate II: The Epochal Wars

Each epochal war brought a particular constitutional order to primacy

|

|

| |

Plate III: The International

Orders

The peace treaties that end epochal wars ratify a particular constitutional

order for the society of states

|

|

| |

Plate IV: Bases for Legitimacy

Each constitutional order asserts a unique basis for legitimacy

|

|

| |

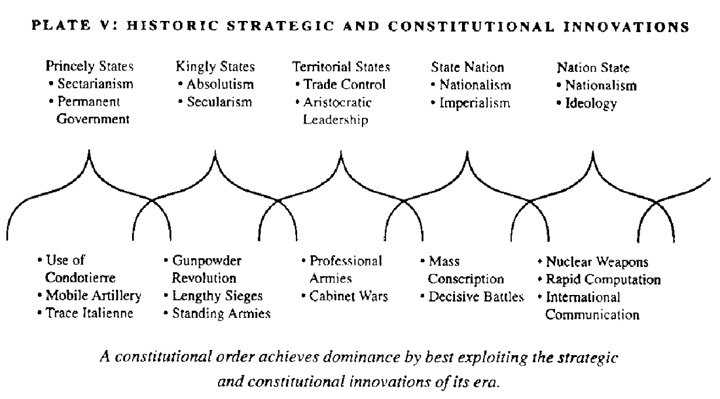

Plate V: Historic, Strategic, and

Constitutional Innovations

A constitutional order achieves dominance by best exploiting the strategic and

constitutional innovations of its era

|

|

| |

Book II: States of Peace:

Introduction: The Origin of International Law in the Constitutional

Order

Professor Bobbitt notes that the Peace of 1990 (with demise of the Soviet

Union) was unexpected and not prepared for. Political leaders are still

thinking in the modes appropriate for the Long War. "This way of thinking

treats states and their interests in much the same way that welfare economics

treats the consumer: the decisions of states are, axiomatically, choices that

define the interests of states, and beginning from the positions of power in

which they find themselves, states have the sole objective of maximizing that

power." "In war strategy takes priority.." But now we must deal

with peace. "Thus the first strategic consequence of the new peace is that

strategy alone must be augmented with law.".. ."Complicating this

resort to law, however, is the fact that international law is itself in flux.

Changes in the strategic environment inevitably produce changes in law, not

simply because law tends to reflect the positions of power in a society -

international society in this instance - but because law itself is composed of

the practices of parties who will necessarily adjust their ambition, their

actions, and their doctrines to take account of changes in the strategic

context."

Dr. Bobbitt elaborates on this theme - that the current institutions for

international law are inadequate. Then he outlines the content of the coming

book.

Part I is devoted to description and analysis of the society of nation-states

and the concepts and programs developed by Colonel House and President Wilson.

"In part II of Book II I will present the origins and development of

international law according to the periods of the constitutional development of

the State described in Part II of Book I."

"In Part II I will argue that the great peace conferences that settled the

epochal wars created the constitutions for the society of states."

"In Part III I will take up the emerging constitution of the new society

of market-states. I will suggest that American principles of limited

sovereignty better serve such a society than the European concepts that

currently structure international law. I will imagine various constitutional

orders of the society of market-states and conclude by arguing that, by varying

the degree of sovereignty retained by the people, states will develop different

forms of the market-state, yielding a more pluralistic constitution for

international society." .

|

|

|

Part I: The Society of

Nation States

"Thesis: The Society of Nation-States developed a Constitution that

attempted to treat states as if they were individuals in a political society of

equal, autonomous, rights-bearing citizens" "In the society of

nation-states, the most important right of a nation was the right of

self-determination". But this posed problems when the population of a

'state' was not one nation. "Given that one purpose of the nation-state

order was to use law in furtherance of the cultural and moral values of the

dominant national group".

"The confusion was seen in the Third Yugoslav War in Bosnia, which finally

discredited the legitimacy of a society of states built on this constitutional

order".

We have seen this even more violently in the current wars in the Middle East

and in civil conflicts inside many other states now. Fundamentally, the problem

is that one cannot have 'nation-states', that is polities whose legitimacy in

the society of states is based on a 'nation' when the population of that polity

is NOT a nation.

|

|

|

Chapter 14 - Colonel

House and a World Made of Law

This chapter of 43 pages includes a brief biographical background on Colonel

House and on Woodrow Wilson and how the two came to work together in pursuit of

their conception of what the 'new world order' should look like. This new order

was to be embodied in the League of Nations.

But they misunderstood the dominant view in the U.S. Congress - the Senate -

which insisted that the U S. Constitution demanded that U.S. participation in a

war required a declaration of war by Congress. So agrement to an international

Treaty that would include participation by the U.S. without such declaration

was unconstitutional and not to be agreed to. Of course we have overthrown this

concept since World War II and that is one of the problems we have

today.

|

|

|

Chapter 15 - The Kitty

Genovese Incident and the War in Bosnia

This is one of the longer chapters and in it the author expounds on several

subjects. He begins with a detailed description of the tragedy of Kitty

Genovese, who was murdered in Queens while numerous witnesses (or individuals

who simply heard her) failed to act. He takes this as a case study in the

psychology of those who fail to act when they well know a tragedy is taking

place. Two psychologists "found that the crowd behavior in the Kitty

Genovese case was very much like that of crowds in other emergency

situations."

"To summarize, we can say that there are five distinct stages through

which the bystander must successively pass before effective action can be

taken."

"So it was with the horrifying events of the three years 1991-1994 in the

former state of Yugoslavia: fascinated, frightened, appalled, the civilized

world was anything but apathetic."

Dr. Bobbitt takes the Genovese incident as a metaphor for the American response

to the Yugoslav war. "When President Clinton said, mistakenly, that the

current conflict in Bosnia-Herogovinia goes back to the eleventh century, he

exposed more than a careless speechwriter of dubious erudition, rather he

showed that he was unable to appreciate just what had happened".

Bobbitt links the psychology of the individual case with that of

the collective case. He then discusses the historical background and the events

and failures in Bosnia. He devotes much space to this study because he

considers it representative of the failure of the nation-state and its society

of states.

"The society of nation-states decides, either in peace conferences like

those at Versailies and San Francisco, or in the ongoing institutions set up by

these peace congresses - like the U.N. - what elements are required for

self-determination."... "By contrast, recognition of statehood on the

basis of the criterion of nationality alone puts the ball in the court of the

State itself."

"Some international lawyers and diplomats behave as though there is a

world order of nation-states that is analogous to the civil order of a society,

and they argue that the international community must respond in the way that a

domestic government responds to criminal behavior. This makes armed

intervention into a kind of police work. If anyone still believed in this

vision of world order in 1992, I don't see how that person could maintain such

a view after Yugoslavia."

|

|

| |

Chapter 16 - The Death of

the Society of Nation-States

Here we come to a critical issue. As the title indicates, Professor Bobbitt

expounds a rather negative view of the future of the nation-state and its

society here. And, of course, he is writing in 2002, before the events of the

past 15 years have exposed his predictions repeatedly.

"The legitimacy of the society of nation-states will not long outlast the

delegitimating acts of its leading members. Serbrenica represents the final

discrediting of that society, because there the great powers showed that

without the presence of the Long War, they were unable to organize timely

resistance even against so minor a state as Serbia when Serbia threatened the

rules and legitimacy of that society. By contrast, in Kosovo, a U.S. led

coalition attacked Serbia to vindicate market-state concepts of sovereignty -

specifically, the novel conviction that a state's refusal to grant rights to an

internal minority renders that state liable to outside intervention."

"As the nation-state increasingly loses its definition, the sharp cultural

borders that, for example, made the Danes different from the Dutch, are losing

legal and strategic significance.... Nation states are too rigid, have too many

rules for behavior including economic behavior, have been captured by special

interests whose welfare demands higher taxes with larger loopholes and more

officious regulations (not limited to economic regulation but including also

for example, hate-speech laws, smoking bans, and the whole panoply of political

correctness, as well as prohibitions against a wide variety of personal

behavior."

"The State has always depended on getting people to risk their lives for

it. Each constitutional order found a way to do this. The nation-state

persuaded people that a state whose mission was the improvement of their own

welfare provided a valid justification for enduring personal jeopardy. If such

a state is no longer able to enforce and sustain national cultural values .....

its claim on the sacrifice of its citizens weakens".

"The shift to the market-state does not mean that states simply fade away,

however."

"In the face of such an historic shift in the constitutional order of

states, the society of states also had to change".

The author then discusses the many failures of the United Nations to fulfill a

role in support of a constitution of a society of nation-states. Moreover the

entire project as seen by President Wilson and Colonel House has

failed.

|

|

| |

Part II: A Brief History

of the Society of States and the International Order

"Thesis: much as epochal wars have shaped the constitutional order of

individual states, the great peace settlements of these wars have shaped the

constitutional order of the society of states."

"The international congresses that concluded peace treaties ending epochal

wars produced the constitutions of the society of states for their respective

eras".

|

|

| |

Chapter 17 - Peace and

the International Order

This is a five page introduction to the following section. Professor Bobbitt

refers again to Colonel House and Kitty Genovese. He remarks that. "The

massacre at Srebrenica will also mark an unexpungable point in modern history,

for it is one of the crucial events in the Yugoslavian Wars that signify the

end of the era of the nation-state."

He reminds the readers,

"In Book I, we have dealt with the relationship between constitutional

change and strategic change, as this relationship affected the individual

state." But what about the society of states? "What provided

legitimacy, however, for the society of states?"

"It is my premise that there is a constitution of the society of states as

a whole; that it is proposed and ratified by the peace conferences that settle

the epochal wars previously described, and amended in various peace settlements

of lesser scope, and that its function is to institutionalize an international

order derived from the triumphant constitutional order of the war-winning

state. Thus while violence and war initiate the process of change in the

constitutional order, peace and law ratify the ultimate result."

"If we take this idea - the creation of a constitution for the society of

states from the settlement of an epochal war - in light of the relation between

such wars and the constitutional order of states, then we can infer that

international law arises from constitutional law."

"This society of states (today) has a constitution, indeed, it has had at

least five previous constitutions. As I have emphasized, every society has a

constitution; to be a society is to be constituted in a particular way."

"Each new period in the constitutional life of the State commenced with a

revolution against an established domestic, constitutional order, though it is

only with hindsight that one may say that a particular revolt led to the

dominance of a particular constitutional form, because many such revolts have

withered, or the forms to which they gave birth have contended with and been

defeated by other forms that became dominant."

"What are the characteristics of a constitution for the society of states?

Like other constitutions, this one sets up a structure for rule following;

allocates the jurisdiction, duties, and rights of the institutions it

recognizes; determines a method for its own amendment and revision; specifies

procedures for coping with disputes arising from its implementation; and above

all, legitimates those acts appropriately taken under its authority."

Further, Bobbitt writes that he will discuss some of the leading interpreters

of international law in each era not because they may have had influence but in

order to understand what international law is.

|

|

| |

Chapter 18 - The Treaty

of Augsburg

Bobbitt begins: "The change in attitude on the part of monarchs and their

counselors reflected the constitutional changes underway at the end of the

fifteenth century."

"The Constitution of 1555: The Peace of Augsburg"

These changes involved the outcome of the Hundred Years' War and the Valois-

Hapsburg wars. It was the French intervention in Italy that created the

struggle which ended with the Peace of Augsburg. This Peace set the

constitutional terms of the new society of states that emerged from this

epochal war. And this was a result not so much from French victories as from

the newly powerful princely states.

"Medieval Christendom had known no society of politically distinct states.

After princely states first appeared in Italy, they gradually spread throughout

Europe, replacing the universal, overlapping structures of ecclesiastical,

feudal society with a discrete, territorial pattern of states." "This

doctrine of the essential separateness of the new states into which Christendom

was now divided was indeed the result of the principle of Augsburg. This

principle, which enshrined the legitimacy of the state sovereignty and denied

the universal order of the Respublica Christiana, replaced that order

with the society of princely states whose horizontal relationship indicated

their mutual sovereignty."

"Consitutional Interpretation: The First International Lawyers"

Bobbitt identifies and discusses four main international lawyers whose

interpretation of the new constitutional order he discusses.

These are Francisco de Vitoria, Francisco Suarez, Balthazar Ayala, and Alberico

Gentili.

Dr. Bobbitt's interpolation of sections on the leading theories proposed to

legitimize the constitutional basis of each new international arrangements with

the excellent descriptions of both the tactical-technological conduct of war

and the changes in state strategy and constitution is a remarkable contribution

to our understanding of military as well as social- political history

|

|

| |

Chapter 19 - The Peace of

Westphalia

Professor Bobbitt begins with description of the collapse of the settlement of

the Peace of Augsburg, which had established the legality of the constitution

of the princely states. This came about when Prince Maximilian of Bavaria in

1608 annexed and re-Catholicized the Lutheran city of Donauworth. Augsburg had

made no provision for the 'seizure' of a city, but had fixed frontiers as of

1552. Most histories set the beginning of the war as 1618 with the

Defenistration of Prague.

"Out of the anarchy that characterized the final stages of the Thirty

Years' War, there arose a stronger, more coherent society of states whole legal

structure was redefined by a new constitution for that society. This

constitution is the set of treaties known collectively as the Peace of

Westphalia."

"The Constitution of 1648: The Peace of Westphalia"

The author recounts the events of the various meetings in Osnabruck and Munster

and the thoughts, policies and roles of the main actors. The results were three

separate treaties. The negotiations were continually influenced by the military

situation as the fighting continued during these meetings. The Swedes, French,

Spanish, Dutch, Italians, individual German principalities and cities, and the

Hapsburg emperor all had their desires (mostly incompatible) and Bobbitt

describes them all. The French and Swedes obtained most of the territories they

wanted. The French had hoped for the complete dissolution of the German empire

into its hundreds of individual polities but accepted the German desire to

remain inside an empire but become sovereign in practice. The Spanish lost

control of the Netherlands which, along with Switzerland gained status as a

state. Significantly, the pope denounced the entire results in a bull, but was

ignored.

"War was recognized as a legitimate form of resolving conflicts. The

concept of just war was nowhere mentioned. It had become irrelevant. No state

was allowed to be destroyed, however, and compensation was to be awarded to

those states that gave up strategically advantageous possessions."

"This last rule is important to stress, as well as its corollary that mere

possession was not equated with legitimacy".

Bobbitt proceeds to discuss the concepts advanced by contemporary commentators.

"The idea of a juridical order without a higher political or

ecclesiastical authority is so novel, and so far-reaching, that it has given

immortality to the name with which it is mainly associated, that of the

seventeenth century lawyer Hugo Grotius."

"Constitutional Interpretation: The International Lawyers"

Professor Bobbitt describes Grotius' life and works. The main concept was that

the states should recognize that it was in their self-interest to conform to

the rules (constitution) set out for the society of states but recourse to war

was included. There was now no higher authority. Bobbitt remarks: "That is

to say, strategy had been severed from law by war."

The other leading lawyer on whom Bobbitt focuses is Samuel von Pufendorf, who

believed that the law of nature provided the only basis for international law.

And he also notes the influence of Pufendorf on Hobbes and Spinoza. But in

conclusion;

"However that may be, the political actors of the time confronted the

problem of post-Westphalian law and order - namely, that in the absence of a

universal sovereign every kingly state, which Westphalia had made the sole

preserver of the liberty, authority, and even the life of the political society

largely composed of such states, would attempt to aggrandize itself to the

limit of its power."

There is much more of both factual description and Dr. Bobbitt's analysis in

this important chapter.

|

|

| |

Chapter 20 - The Treaty

of Utrecht

In this short chapter Professor Bobbitt continues his analysis of the impact of

the settlement of an epochal war as seen in the peace treaty.

"The Westphalian Problem - that absent an absolute and universal

sovereign, every kingly state would attempt to aggrandize itself to the limit

of its power - found its most threatening expression in the campaigns of Louis

XIV that directly challenged the Westphalian settlement. The solution to this

Problem was ultimately expressed in a series of eight treaties known as the

Peace of Utrecht, which resolved the epochal war composed of Louis's

campaigns."

"The Constitution: The Peace of Utrecht"

The author briefly recounts the events of these wars and then moves to the

'constitution' that came out of the peace treaties.

"The Peace of Utrecht consists of eleven separate bilateral treaties. That

it represented a constitutional convention of the kind that had met at

Osnabruch and Munster was well recognized by the parties"... ."There

was a general distinction drawn by the statesmen at the congress between the

'private' interests of the states involved in the negotiations and the 'public'

interests of the society of the states of Europe as a whole."

"The language of the new consensus was reflected in four striking

contrasts with the idiom it superseded." "First, the language of

'interests' replaced that of 'rights." "Second, aggrandizement - so

integral to the stature of the kingly state - was replaced by the goal of

secure 'barriers' to such a degree that claims for new accessions were

universally clothed in the language of defensive barriers." "Third,

the word state underwent a change. A 'state' became the name of a

territory, not a people, as would occur later when state-nations began to

appear, not a dynastic house as was the case at Westphalia." "Fourth,

whereas the kingly states had seen a balance of power as little more than a

temptation for hegemonic ambition to upset, the territorial states viewed the

balance of power as the fundamental structure of the constitutional system

itself."

"At Utrecht, a new conception of the balance of power made its historic

debut. Its novelty arose from the change the states of Europe were undergoing

in their domestic constitutional orders. As the territorial state replaced the

kingly state, the idea of the 'balance of power' moved from providing the

occasions for sovereign action to animating a constitutional structure for

collective security itself."

As always, Bobbitt describes in detail the thoughts and actions of the leading

individuals who created the new system. He then moves on to discuss the

interpretations of this constitutional system by international jurists.

He notes first that:

"Territorial states are so named owing to their preoccupation with the

territory of the state." "The territorial state aggrandizes itself by

means of peace because peace is the most propitious climate for the growth of

commerce." "The new perspective, with its emphasis on human freedom

and the role of human perception, was crucially influential in the work of the

two writers who dominated international jurisprudence during the era of the

territorial state: Christian Wolff and Emmerich de Vattel."

"Consitutional Interpretation: The International Jurists"

"The balance of power was a constitutional concept for the society of

European states, and also, as we saw in Book I, played a similar role in

ordering the internal relationships of the states that composed that

society". "Territorial states are so named owing to their

preoccupation with the territory of the state".

"The territorial state aggrandizes itself by means of peace because peace

is the most propitious climate for the growth of commerce".

"Christian Wolff"

"Born in 1676, he ultimately became the principal apologist for the

territorial state and came to regard Frederick the Great as the model of a

'philosopher king'".

"Emmerich de Vattel"

"He was born in the Swiss principality of Neuchael" "In this

work, (Le droit des gens; ou principes de la loi naturelle appliques a la

conduitet aux affaires des nations et des souverains), Vattel proposed to make

Wolff's ideas on the law of nations accessible to 'sovereigns and their

ministers'". "Following Wolff and Leibniz, Vattel wrote that the

duties of a state toward itself determine what its conduct should be toward the

larger society of states that nature has established. And what is that? Each

state must strive to develop as well as to protect, its existence,".

And there is much more to Vattel that Bobbitt explains.

|

|

| |

Chapter 21 - The Congress

of Vienna

Professor Bobbitt begins by reminding readers that his view of the Wars of the

French Revolution and Napoleon as stated in Book I is different from the

standard establishment view.

"All the wars of France during this period were fought in order to

obligate the mass of persons to the French state." "The wars of

1792-1815 between France and various coalitions of other European powers were

united, strategically and constitutionally, by the political program of the

French Revolution. This program sought an end to the territorial-state

autocracies and the replacement of these regimes by government in the name of

the people, based on the people's political liberty and legal equality."

The other states sought as best they could to copy the French. The Prussian

reforms were designed for this as Clausewitz noted. The conclusion of the war

brought about the Congress of Vienna at which a new constitution of the society

of states was promulgated - a constitution for a society of state-nations. This

new form then would be the basis for determining the legitimacy of states.

"The Constitutional Convention: The Congress of Vienna"

"Vienna performed the constitutional functions for the nineteenth century

society of states that Augsburg, Westphalia, and Utrecht had performed in

earlier centuries."

"These principles awaited a constitutional convention to give them legal

status. Thus, once again, war and constitutional change were followed by a

peace settlement that took the form of a constitutional convention for the

society of states, including even states that were not parties to the

conflict."

The author proceeds to examine the constitutional convention at Vienna in

detail, describing the motivations and actions of the principle participants.

"The demand for an institution that was purposefully designed to deal with

future conflicts arose in several ways. First it was apparent that the

Utrechtian system had failed. .. Second the mentality that arose with the

state-nation could not passively accept an international system that seemed to

depend upon etiquette for its operation. ... Third, state-nations claimed to

rule on the basis of the consent of the governed."

Bobbitt describes a 'need for a new politics' and a 'need for new principles' -

and the concept of 'balance of power' plus 'the general interest'.

]Dr. Bobbitt writes about two topics - "The Need for New Politics"

and "The Need for new Principles"

"The State-Nation"

"The Constitution: The Final Act at Vienna"

"As we have seen, the Congress of Vienna was not the first such convention

to define the legitimate constitutional form of government for member states,

but it was by far the most intrusive."

He discusses the content of the final act in detail.

"Constitutional Interpretation: The Law Professors"

Again, Professor Bobbitt turns to discussion of the constitutional

interpretations of Vienna by law professors. The first of these is John Austin

and he is followed by Johann Bluntschli. And Bluntschil's ideas had influence

in the United States. However, his concept and that of the Concert of Europe

itself depended on there being a harmony amongst the actors (major powers).

With the creation by Bismarck of the German nation-state this harmony ended.

"The Concert, however, had ceased to function as an institution of

European politics."

|

|

| |

Chapter 22 - The

Versailies Treaty

Professor Bobbitt begins this study of Versailies with a quotation from

Nietzsche denouncing the state-nation at the time Bismarck was creating the

nation-state. Bobbitt then recapitulates the description of the promises of the

nation-state - to provide social security and all the trappings of the welfare

state we know.

"The shadow of the nation-state is its ideology: by setting the standards

by which well-being is judged, ideology explains how the State is to better the

welfare of the nation. Whereas the state-nation had studiedly contrived to

legitimate itself through the creation of a certifying club of other

state-nations, admission to which stamped the state as the representative of

the nation in whose name it ruled, the nation-state could not resort to this

method. It tried this tactic, as we shall see. At Versailies in 1919, and still

later at San Francisco in 1945, the great powers tried to reproduce the

authorizing society that would legitimate their claim to rule, as their

predecessors had done at Vienna."

"Although Versailies agreement might have been a constitution for the

society of states in the way that the peace agreements at Westphalia and Vienna

may be said to be, it can be quickly shown that this was not quite the

case." It did not constitute a settlement consensually agreed to by the

great powers who fought the war.

"The nation-state pursued a new bargain with the nation: in exchange for

the release of enormous national energy, the State harnessed itself to the

nation, promising more than simply its own aggrandizement and glory, it

promised actual improvement in the material well-being of its citizens. Because

the lot of all the citizens of a state can seldom be simultaneously improved,

and because most governmental decisions produce losers as well as winners, such

a task inevitably brought divisive pressures to bear within the State."

Bobbitt proceeds to describe the specifics of the Versailies agreements and

notes the reaction in Germany. The victors lost sight of the purpose to create

a constitution for the society of states. The allies were themselves divided.

And Russia opted out completely. The author discusses Lord Keynes's commentary

also.

"Weimar"

He then discusses the Weimar Republic and notes that in contrast to Westphalia

and Vienna at Paris in 1919 no constitution was created for Germany. He

narrates the resulting political events leading up to the Nazi coup and

Hitler's program.

"Constitutional Interpretation: The Legal Philosophers"

Next, the author turns to the constitutional interpretations of legal

philosophers. Once again some of these names will be unfamiliar to even

well-informed students. He begins with Georg Jellinek. Then he turns to Hans

Kelsen. Next come Marxists, pragmatists, nationalists, neo-Kantians and then

Carl Schmitt, a full Nazi apologist. Bobbitt then turns to the Frankfurt School

and Otto Kirchheimer ( a Marxist group that included Herbert Marcuse and Felix

Adorno). During the later 1930's and WWII these folks became influential at

Columbia University.

"The Weimar experience thus provides a national microcosm of an

international phenomenon, the unstable competition among ideological forms of

the nation-state that occurred in the aftermath of Versailies."

This section provides great enlightenment into the legalisms - the theories -

that claimed to justify Nazism and legitimate its government

philosophy.

|

|

|

Chapter 23 - The Peace of

Paris

The author continues with a detailed discussion, narrative of events and

results, and analysis of these.

"The Peace of Versailies did not bring closure to the epochal conflict

that had begun in August 1914. Like earlier international constitutional

conventions, Versailies enshrined a new constitutional order, which was the

nation-state. But the nature of this form of the state required a further

decision among ideologies, and with respect to this decision, Versailies was

premature."

Namely, there were three competing ideological conceptions about this form -

parliamentary democracy, fascism, and communism. But as a result of the Long

War fascism and communism were finally defeated. Professor Bobbitt describes in

detail his views on, 'What brought about the end of the Long War and the

adoption of the parliamentary nation-state.?' He believes both the 'standard'

accounts popular today are faulty or wrong.

"The End of the Long War"

"I propose, however, to offer a somewhat different account. The two

approaches I have thus far described are the consequence of separating strategy

and law. The former treats international relations as driven by the strategic

requirements of force and the relative comparison of capabilities

alone."... "The second approach treats constitutional developments as

causing, but not caused by, international change."

Professor Bobbitt's conception is very complex, involving interactions between

domestic and international political and economic events in both the Soviet

Union and the United States. As always he places great emphasis on individuals

and their personal choices when confronted with crises demanding decisions.