| |

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR TROOP CONTROL IN OPERATIONS

|

|

| |

I. GENERAL

|

|

| |

Essence and Content of Troop Control: Definition

Troop control is leadership and the special duty of the commander, staff,

chiefs of arms and services political organs, and other control organs of the

headquarters on the creation and maintenance of high combat readiness; detailed

organization of combat operations and actions; direction of operational

formations, large units, and units during operations; and application of their

force to the successful completion of the appointed missions. In the content of

troop control the following collection of missions and methods are most

important:

preserving the morale and political condition of the forces and raising their

combat readiness to accomplish missions;

constantly collecting, analyzing, and organizing situation data in order to

understand the intention and concept of the enemy; (On the basis of observing

and analyzing all indications of the situation the commander can understand the

intention and the concept of the enemy command);

making a timely decision for the operation;

issuing combat instructions to the subordinate forces;

planning the operation (combat);

establishing the troop control system including command posts and

communications system;

guiding and directing the preparation of the forces for the accomplishment of

the combat missions;

organizing and preserving timely, constant interaction;

establishing all around support of combat actions;

controlling troops during the operation;

providing monitoring of mission fulfillment and rendering assistance to the

subordinate forces.

Troop control is accomplished by the commander personally or with the staff,

deputies, and chiefs of arms and services, chiefs of special troops and

services, and in accordance with orders, directives, and instructions from the

higher commander.

The basis for troops control is the commander's decision. In accordance with

the commander's decision the staff organizes and directs all measures for

preparing troops for completion of the mission and directs them during the

course of the operation.

Principles of Troop Control

The following are the main principles for troop control:

one man command and responsibility;

centralized control of all levels with attention also to giving the maximum

possible initiative to subordinates for fulfillment of various missions;

stubborn persistence, activeness, and energy in putting the decision into

practice, ie. executing it;

agility and ability to react to changes in the situation;

continuity and secrecy;

The commander is responsible for making the decision. He answers personally for

effectively using all subordinate forces and properly achieving the results

required in the mission.

Basis and Requirements of Troop Control in Contemporary

Conditions

Troop control in contemporary conditions must be exceptionally effective to

enable the commander to control subordinate forces well in difficult conditions

of combat action. The required characteristics include the following:

vigilance and activeness of control - In contemporary conditions the high

maneuver capability of forces has increased and the combat situation quickly

changes. The rapidity shortens the time element. The struggle to gain time in

order to overtake the enemy in conduct of actions has a deciding influence on

the outcome of the battle. Therefore special attention on the part of the

control organs must be paid to the need for activeness and vigilance.

the expansion of the volume of troop control and requirement for

resourcefulness - The capabilities, qualifications, and extensive experience of

commander and staff in making rational and correct decisions, quickly issuing

missions to subordinates, and taking the best measures with the aim of all

around support of the operations (battle) are important requirements.

higher combat readiness of command-posts and troop control system at all levels

(echelons) - The timely preparation and deployment of a strong control system

starts at front and goes down to the company and platoon levels.

Higher combat readiness is required of all control points and all signal

systems and systems of data collection. They must scientifically analyze data

and issue deductions about situation data quickly and correctly.

reliability (continuity) of control of forces - This is provided by thorough

awareness and correct understanding of the situation on the part of the

commander and staff, by their capability for forecasting likely changes in the

situation; by insuring reliable and continuous communications with

subordinates; for timely relocation of control points moving forward with the

forces; and by constant exchange of data among the staff and higher and lower

forces.

firmness (strength) and strong control of forces - This is making the decision

and putting it into practice with the aim of fulfilling the given mission. This

requires great perseverance, high morale, exactitude, and strength of commander

and staff in executing the decision and a strong will in the face of

difficulties. It is shown by the constant influence of the commander and staff

over their subordinates and forces, by their rendering assistance to

subordinates for accomplishing missions, and by inspecting the execution of

missions.

flexibility of control - This is insured by the great capability of the

commander and staff in quickly influencing newly arising situations and in

their making alterations in previously made decisions or making new decisions

in answer to new situations. They also constantly inspect the execution of the

assigned mission. The commander and staff must collect new data on the

situation, analyze it, and quickly and correctly respond to the situation by

taking needed measures.

centralized troop control - This is unity of the actions of subordinate forces

and concentration of their actions according to a unified plan, in order to

achieve the general objective of the operation (battle) as defined by the

higher commander. Various types of forces and different kinds of combat

equipment participate in combat actions spread over a large region. This

demands unity and centralized control and concentration of all arms and means

with the aim of accomplishing the general mission.

initiative - One of the characteristics of contemporary combat and operations

is increased capability for rapid maneuver of forces and quick changes in the

situation. This requires great initiative of the subordinate commander to

continue the operation in the absence of communications with the higher

commander. (Don't reproach the person who can't destroy the enemy but reproach

the man who is afraid to take responsibility in the required moment and fails

to use all his forces and means and capabilities for destruction of the enemy

and fulfilling the mission.)

secrecy of troop control - Expansion of the enemy's detection and

reconnaissance means requires (demands) strong observation and attention to

taking measures for secrecy. Secrecy of troop control is achieved by the

following measures:

strictly observing security;

observing measures for maskirovka and secret location for control

points;

observing rules for protection of secrecy on the part of individuals who work

in the troop control system;

limiting the number of individuals who are called on to participate in

preparation and planning of operations (battle).

The Relationship of Staff Officer and Commander

The Soviet officer selection system looks for dedicated communists who are

aggressive, tough, stubborn, and with a personality to be a combat leader in

command positions for promotion. Senior commanders (army and above) owe their

positions to personal politicking, favoritism, cronyism and party loyalty. The

senior positions are all under the system of appointments within the

"nomenclature". Not all commanders are intellectuals but all have

attended the vigorous studies at the Voroshilov Academy.

In practice the army commander depends on his staff for the quality of his

planning. Staff officers are career specialists who are academically inclined

and well versed in Soviet terms. They too are taught to follow "the

book" and think in terms of norms and formulas.

The chief of staff is the key individual at headquarters. He advises the

commander during the initial decision process, plans the planning process,

transmits the commander's guidance to the staff, supervises the planning and

recommends the selected course of action to the commander.

The commander always has the final word on a plan. But generally he will accept

the plan proposed by the chief of staff. The commander actively supervises the

headquarters, makes personal field reconnaissance, and keeps fully informed of

all details.

The commander and chief of staff must think and act in unison. They share a

common perception of the unit mission and concept of the operation. The chief

of staff is also the principal first deputy commander and the only one

authorized to act in the commander's name. The other first deputy commander is

concerned primarily with training and combat effectiveness.

The Soviet social system stresses the importance of prerogatives associated

with each position. Thus the interpersonal relations of commander and staff

will be very formal in most cases. Soviet officers are expected to perform

according to rigorous standards.

Staff officers will be trained to perform one specific functional duty very

well but may be cross-trained into another. In addition staff officers will be

assigned specific extra topics to study, such as mountain warfare.

The Soviet system establishes close direct ties between staff counterparts at

each headquarters up and down the line. Thus, while the commanders are passing

combat orders the staff sections will be in communication discussing their

particular parts of the operation (battle).

Commander's Responsibility and Independence

The commander cannot change his mission without approval from higher

headquarters. In his various reports to headquarters he must state his decision

at the time and may make suggestions for future action, which might include

changes to the original plans. He may change things within his division such as

the allocation of his artillery. He could not change the fire plan of a

supporting army's artillery without first receiving permission from the army

chief of artillery and rocket troops, as such a change might affect the army

plans. The division commander may ask adjacent divisions for permission to send

forces through their zones in a maneuver, but this also should be cleared at

army level. The main thing is that the division commanders (all commanders)

know the CONCEPT OF THE HIGHER COMMANDER and stick to

performing their role in it. As long as he keeps in the framework of the higher

commander he can do as much as he pleases or is required. If communications are

cut, he will continue to follow this concept and be as aggressive as possible

in the situation.

Courses of action available to overcome difficulties include: (l) a call for

help; (2) request artillery or air support; (3) commit reserve; or (4) regroup

forces.

Initiative

How much initiative is allowed to the army commander and staff? The

front commander and staff will let the army commander do what he

wants...as long as the front does not know about it. If the

front staff does know about it, they will usually have an opinion on

how to do it and will say so. If the army suggests doing something the

front did not already know about or specify, the front will

generally say "fine that is the way we would like to do it"; the idea

being to preserve the appearance of the front being in charge and not

let the subordinate think he is getting away with anything.

There is massive mistrust throughout all echelons of the Soviet military just

as there is in civilian society at large. No one trusts anyone in reports;

cheating is expected. No one relies on promised support and, in fact, everyone

is admonished to do their job without expecting, relying on, or receiving

support. Commanders expect that if they do not do things themselves they might

be betrayed. The chief of the political department of each staff, while not

being able to give much advice, will be reporting and will try to ensure

reports are not falsified.

Independent Action

The question frequently raised is, "How much independent action is allowed

to Soviet commanders in making decisions involving changes to plans and would

they really take such action?" The answer lies in a consideration of the

mission. The mission must be accomplished in, by, and at a certain time. Any

initiative on the part of commanders can be supported if it will help achieve

the mission including its time element. If the change is major, and especially

if it involves a different time, the commander will send a representative to

higher headquarters to obtain authorization for the change.

If the army commander wants a change in the plan, he must obtain the permission

of the front commander; and, if the latter wants a change, he must get

TVD or general staff approval, as such a change will involve the higher

headquarters and may force changes in the overall plan. The front

commander alone cannot make such a decision. If the mission is not affected,

then he can make changes, but even then he would have to be very cautious. The

highest credit goes to people who do as ordered despite all obstacles.

There is always a psychological relationship between the commander and his

superior commander. It may be that the higher commander is so dependent on his

staff for making his plans that he cannot easily evaluate the proposal of the

lower commander. Rather than show this, he will let it become clear that he

does not appreciate proposals for changes. Some commanders will do their utmost

to avoid making changes just to appear firm and decisive. Unless the situation

is serious, and the consequences of not changing dangerous, the subordinate

commander would have to know if his boss does in fact like to hear proposals

for changes before he would offer any. Only a commander with a very strong

personality could accept suggestions from subordinates to change.

Headquarters Organization

The Soviets consider the headquarters to contain six basic elements. These are

the commander, the staff, the political section, the special

(counterintelligence) and legal sections, the sections of the chiefs of arms

and services, and the section of the chief of rear services. This organization

is shown in the following table.

|

|

| |

|

BASIC ELEMENTS OF HEADQUARTERS

|

| Unit |

Regiment |

Division |

Army |

Front |

| Elements |

Commander |

Commander |

Commander |

Commander |

| 1 |

Staff |

Staff |

Staff |

Staff |

| 2 |

Political subsection |

Political section |

Political department |

Political directorate |

| 3 |

Agents of special section |

Special section |

Special section |

Special section |

| 4 |

Investigators |

Military Prosecutor - Tribunal |

Military Prosecutor - Tribunal |

Military Prosecutor - Tribunal |

| 5 |

Deputy commanders or chiefs of arms and services |

Deputy commanders or chiefs of arms and services |

Deputy commanders or chiefs of arms and services |

Deputy commanders or chiefs of arms and services |

| 6 |

Deputy commander for rear service |

Deputy commander for rear service |

Deputy commander for rear service |

Deputy commander for rear service |

Figure 1 Basic elements of headquarters organization

|

|

| |

Command and Lines of Subordination between

Headquarters

The term command is defined by the Soviets as the person or group of persons

exercising direct command control of the troop unit. There is also a secondary

command system for the various special elements of the Soviet headquarters. The

command is the element of the headquarters which not only has primary

responsibility for overall success or failure, but also for direct personal

control of troops during all phases of a combat action and for their training

prior to combat.

At various levels the organization of the command will vary. The following is a

typical command organization for the division and army headquarters. In

addition to the command chain of command there is a special functional chain of

subordination directly between the chiefs of combat arms, special troops, and

services and rear and their counterparts above and below. This dual

subordination plays a key part in the promolgation of orders and instructions

as will be shown in subsequent chapters. This complex arrangement is shown in

Figure 2.

|

|

| |

Figure 2 General form of command and special

subordination

Axis Officers

Axis officers are used as an auxiliary means for troops control and

communication between headquarters. There are two types of axis officer. The

first type, capped "command axis officer" is assigned from higher to

subordinate or adjacent headquarters. The second type, called "axis

officer", is assigned from subordinate or adjacent headquarters to the

liaison group in the higher headquarters.

Command axis officers usually are selected from the operations section of the

higher staff for temporary liaison to the lower headquarters. Their duties

include:

transmitting and explaining to the subordinate staff and commander the orders

and directives of the higher commander; reporting to the higher commander the

current situation and needs of the subordinate unit; observing the decisions

and actions of the subordinate commander and keeping the higher commander

informed concerning these decisions and actions; ensuring proper execution of

the orders of the higher commander by the subordinate units;

Axis officers are selected by the chief of staff from the major staff sections

including operations intelligence communications and usually work as a group

with the higher operations section. Their duties include: reporting to the

higher staff as required the current enemy situation in the subordinate unit's

sector; reporting the tactical situation of the subordinate unit and the

decisions of the unit commander, the chief of staff, and the chief of the

operations section; reporting to the subordinate staff, as directed,

information from the higher staff concerning the enemy situation, tactical

situation, and decisions of the higher commander; sending timely warning to the

axis officer's unit concerning impending missions and ensuring prompt delivery

of all orders and directives from the higher headquarters.

|

|

| |

Command Posts

The Soviets emphasize the extreme importance for the proper functioning of the

headquarters that it be correctly echeloned, arranged, and equipped. The site

must be carefully selected and skillfully camouflaged. Movement from one site

to the next is carefully planned by the staff and prepared for by special

engineer and signal units.

The command post is located in a place convenient for directing subordinate

units during the operation. Generally this means that it must be a convenient

location for establishing reliable wire and radio communications. Another

important feature of the command post area is that it should afford convenient

routes of approach to and from subordinate forces. The command post is located

near the concentration for the main effort. The Soviets emphasize the necessity

for taking advantage of natural camouflage and natural obstacles in locating

the CP. They warn against locating the CP in any readily identifiable area such

as conspicuous hills or crests, edges of woods or in conspicuous clearings or

groves. Often the CP is located on the reverse slope of an elevated area

covered with bushes,

The main components of the command post are the commander's command center, the

operations group, the communications center, and the service group. Depending

upon the terrain, the command post is arranged generally as indicated in figure

--. Dugouts, covered shelter trenches, open trenches, and weapons emplacements

are all used to shelter command post personnel and installations.

The command post operations group is composed of those officers and staff

sections directly concerned with the direction of combat operations. These

include: the commander, deputy commander, chief of staff, operations section,

intelligence section, topographic section, communications section,

cryptographic section, artillery commander and staff, chiefs of arms and

services and staffs, a staff officer from the rear service area, liaison

officers, and the staff duty officer.

The communications center includes the installations and units primarily

concerned with providing communications for the commander and staff with

higher, lower, and adjacent headquarters. The commander of the signal unit is

the director of the communications center. All units servicing the

communications center are subordinate to him and he in turn is subordinate to

the chief of communications at the headquarters. The communications center

includes the radio center, central telephone-telegraph station, landing strip

and air ground communications point, message center, and reserve communications

supplies and personnel.

The Command Post Guard and Defense System

The all around protection of the command post area is provided by organizing a

guard system and a defense system. In combat, the command post is located in an

area which is protected from ground attack by the troops of subordinate units

and from air attack by the unit's air defense units. However, the command post

also plans its own guard and defense systems. This planning is accomplished

mainly by the operations section, and execution of the plan is supervised by

the headquarters commandant. In addition to personnel from the headquarters

commandant unit, staff personnel also participate in the command post defense,

especially in the event of an enemy breakthrough. In this case, the guard and

defense system is often reinforced with small infantry, artillery, and engineer

units.

An important part of the command post administrative organization is the duty

officer system. In order to assure continuity of the command post work, to

provide rest for the command and staff personnel, and to facilitate the sending

and receipt of messages and documents, duty officers are appointed to vital

command post positions every 24 hours. The duty officer system includes the

operations section duty officer, the communications duty officer, and the

message center duty non commissioned officer.

Location of Command Posts

Soviet regulations provide general norms for the location of command posts

under various conditions. Commanders must locate themselves as far forward as

possible in order to exert personal control of the most important combat

actions. The following table indicates the approximate distance from the front

lines to the forward and main command posts and the rear service control point.

These distances are subject to considerable change owing to varying

circumstances in combat. The command posts are displaced in a planned, orderly

manner in order to remain within prescribed normative distances from the

advancing troops. The formula for determining how long a command post may

remain in one location in relation to the rate of advance of the front line is

given in Chapter Six.

|

|

| |

DISTANCE OF COMMAND POST FROM FRONT LINE

|

|

In the attack |

In defense |

|

Forward CP |

Main CP |

Rear CP |

Forward CP |

Main CP |

Rear CP |

| Regiment |

-- |

4-6 |

12-15 |

2-3 OP |

5-7 |

12-15 |

| Division |

4-6 |

10-12 |

30-40 |

6-8 |

12-15 |

30-40 |

| Army |

10-15 |

30-50 |

40-60 |

15-20 |

40-60 |

50-70 |

| Front |

35-50 |

100-150 |

120-170 |

45-65 |

100-150 |

120-170 |

Figure 3 Locations of command posts

|

|

| |

II. CONSIDERATIONS IN ORGANIZING AND PLANNING

OPERATIONS

|

|

| |

Characteristics of Modern Combat

The Nature of Offensive Battle

The essence of offensive battle is to hit the enemy with heavy fire of all

types of weapons, (including nuclear weapons when used); to attack resolutely

and relentlessly, moving continuously attacking troops into the depth of the

enemy dispositions to seize and destroy his personnel, weapons, and combat

equipment; as well as to capture important areas and lines in the depth of the

enemy defenses.

The Aim and Components of Offensive Battle

The aim of offensive battle is achieved through a combination of heavy fire of

all types of weapons; forceful blows by tank and motorized rifle formations,

units, and subunits to an extended depth in cooperation with the air forces;

use of extensive maneuver of fire, troops, and means on the battlefield; and

aggressive support by radio-electronic combat.

The aim of offensive battle for ground forces is to destroy specific enemy

groupings at a certain time and seize favorable lines and areas in the depth of

the enemy defenses.

The inherent components of offensive action consist of fire, blow, maneuver,

and radio-electronic combat.

Fire provides the possibility to insure the neutralization of the enemy and

provide favorable conditions for the enemy's destruction by a blow of tank and

motorized formations. In a nuclear war the principal element of firepower is

the nuclear strike, while in a conventional war firepower is based on artillery

and air force strikes. It must be noted that a defending enemy can also fire to

destroy the attacking forces by means of fire, therefore an intensive fire duel

ensues during the battle. In order to establish a superiority of fire over the

enemy, the attacking troops can be supported by such an amount of artillery

which will establish a favorable correlation in terms of artillery for the

attacking troops. It must also be noted that the attacking forces, when in the

depth of the enemy area, will have to relocate their artillery more frequently

that the defending troops; therefore, an appropriate superiority of artillery

over the enemy should provide conditions for the establishment of sufficient

artillery support for the attacking troops during all phases of an offensive

battle.

The blow is a combination of fire with the movement of tank and motorized rifle

subunits, which leads to the complete destruction of the enemy or his capture

and seizure of favorable lines in the enemy's defenses. The blow is actually

fire of machine guns, guns, automatic rifles, and other small arms mounted on

tanks, BMP's, APC's, and other vehicles or used during movement in direct

contact with the enemy or used by dismounted infantry during the assault. Its

nature is based on the fact that it is fire on the move in direct contact with

the enemy. In other words a blow is assault or counterassault.

Maneuver provides favorable conditions to launch blows against the enemy and

fire effectively on the enemy. Maneuver enables the troops to get into a

position from which they can effectively attack the enemy or launch a

counterattack or deliver effective fire against the enemy. Maneuver also is

conducted to move the troops quickly during the advance in depth, and to

outflank the enemy dispositions. Maneuver can be conducted by fire, troops, and

means. The principal forms of maneuver at the tactical level are envelopment,

deep envelopment, and penetration.

When the envelopment of the enemy is not feasible, its defenses are attacked

using the penetration method. The role of penetration is to create gaps in the

enemy defenses by destroying its personnel and equipment by fire, to move the

attacking forces through the entire tactical depth of the enemy defenses with

simultaneous expansion of the attack to the flanks, and further development of

the attack to the depth. The action of the troops in a penetration is of the

nature of maneuver. The troops continuously seek gaps and openings in the enemy

dispositions to conduct envelopment, and deep envelopment which will lead to

the encirclement of the enemy grouping.

On the modern battlefield radio-electronic combat constitutes a new dimension

in the basic components of offensive combat. Radio-electronic combat is aimed

at interrupting the enemy command and control and weapons control systems and

to protect friendly systems from enemy reconnaissance, jamming, and

radio-electronic suppression. The following factors contribute to success in

offensive combat: continuous and aggressive reconnaissance;

neutralization of enemy defenses by heavy fire;

swift advance through ruptures and gaps in the enemy defenses;

penetration of defensive lines and crossing of water obstacles in the depth of

the enemy from the line of march;

continuous intensification of the efforts by the second-echelon and reserves

and maneuver by forces and means;

decisive repulsion of counterattacks and relentless pursuit of the retreating

enemy;

quick negotiation or bypass of obstacles and contaminated areas;

continuous maintaining of coordination (interaction);

firm and flexible troop control;

quick restoration of the combat capability of the troops.

The principal difference in offensive combat with the use of nuclear weapons

from combat without their use is the fact that in a nuclear combat the enemy's

defenses are destroyed simultaneously and the action of the troops is

coordinated in a way to quickly exploit the impact or consequences of the use

of nuclear weapons, while in a non-nuclear situation the enemy is destroyed

successively with the action of the troops coordinated with artillery fire and

air strikes.

The Conditions and Form of Initiation of the Attack

The offensive operation is conducted under various kinds of conditions and in

different situations depending on the enemy, terrain, time, season, weather

conditions, and tactical situations. The attack can be conducted against a

deliberate defense or a hasty defense. It can be conducted in an open terrain,

mountains, deserts, etc. It can be launched during the day or at night and in

various seasons and types of weather, such as arctic conditions and tropical

climates. All these conditions will have influences in one way or the other on

the missions of the troops, combat formations and groupings of troops, and

methods of coordination and initiation of the attack.

Generally speaking, the attack can be initiated either from the line of march

or from a position in contact with the enemy. Each of these forms will have

other variations depending on the tactical and operational situation.

Each form has its advantages and disadvantages. For example, the attack from

the line of march, being the principal form for the initiation of the attack in

modern times, provides a surprise blow to the enemy by the movement of the

troops from the depth to concentrate them for a penetration. It also precludes

the concentration of large groupings of forces in close contact with the enemy

for longer periods of time and prevents the enemy's reconnaissance from

locating all targets of the attacking forces well in advance. This also cuts

the volume of engineer work to provide cover for the troops concentrated in

direct contact with the enemy.

The disadvantages are the requirement of sufficient road network for the

movement of all types of troops for the attack during the artillery preparatory

fire period, which may not be available in some mountainous terrain; absence of

conditions for the troops to study in detail the enemy's defenses sufficiently

before the attack; and requirement for strong air cover to protect the troops

during their advance to the assault against enemy air strikes.

While in WWII, when the firepower of the divisions had not sufficiently

developed, the principal part of the attack against a prepared and fortified

enemy defense was from a position in close contact with the enemy and against a

hasty enemy defense was attack from the line of march; the situation has

changed today. Now the improvement and increase in firepower in the division

and the high maneuverability of the troops makes it possible to attack a

prepared and even fortified enemy defense from the line of march. In this case

the troops move from the depth during the artillery preparatory fire to the

assault line; and, while the enemy is suppressed by artillery and air force,

the troops successively deploy into battalion, company, and platoon columns and

finally deploy for the assault and initiate the assault without pause. During

this advance, the line of deployment to battalion columns is selected to be out

of range of the main enemy artillery groupings. The preparatory fire for the

attack normally begins when the troops reach this line. In other words the

distance of this line from the enemy FEBA can be eight to ten kilometers. The

line of deployment into company columns is selected to be out of range of enemy

antitank guided rockets and tanks and guns conducting direct fire. In other

words it is currently three to four kilometers from the FEBA. The full

deployment line (combat line) is selected to be behind the last sheltering

terrain feature or one kilometer from the FEBA. This can also serve as an

assault line in an attack in mounted attack. In dismounted attack the assault

line is selected as close to the enemy as possible and also a line of

dismounting is selected. When the attack from the line of march is conducted

against a prepared defense, the attacking troops will occupy assembly areas to

prepare the attack in areas located out of range of the enemy tactical rockets

and long range artillery. In the course of the offensive operation the

preparation for the attack against a hasty defense line is conducted while the

troops are still moving toward the line, so they can launch their attack

without stopping. In cases when the attack on the move from the depth is not

successful, the attack is done after a brief preparation. This preparatory time

is 2-3 hrs for regiment, and 4-6 hrs for division, during which artillery

preparation is conducted and adjustments in groupings are made, while further

reconnaissance of the enemy is continued.

When the troops move from the depth to attack the enemy prepared defense,

artillery groups, part of the direct fire weapons, part of the air defense

troops, and control points move in advance to the starting (departure) area.

The artillery should be moved early, to be prepared to fire two to three hours

before the beginning of the attack.

The attack from a position in close contact with the enemy can be conducted

either from the defensive positions or after the relief of troops in place. In

the first case a regrouping is required as part of the preparation for the

attack, while in the second situation a relief in place is organized and

conducted prior to the attack. In either case the troops thoroughly study the

enemy defensive dispositions and organize the attack on the ground. In order to

decrease the effects of enemy fire on the troops during the preparation of the

attack, the time of concentration of the troops should be cut and shelters and

cover should be provided in the departure areas for personnel and equipment.

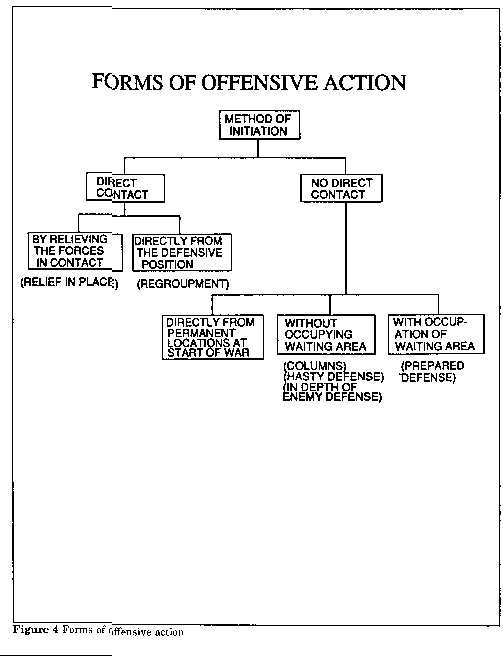

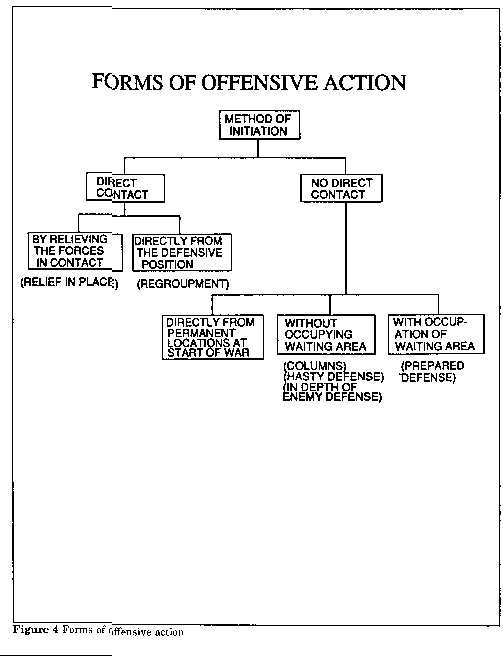

(The various forms for offensive actions are shown in Figure 3).

By the same token attack from the position in close contact with the enemy has

its advantages and disadvantages, which will correspond to the opposite factors

mentioned with respect to the attack from the line of march.

|

|

| |

Figure 4 Forms of offensive action

Terminology of Missions

A squad, platoon, and company have immediate missions and a direction of

attack. A battalion and regiment have immediate and subsequent missions and

direction of attack. A division has immediate and subsequent missions. The army

has immediate and longer range missions. The latter is the final mission of the

army operation. The front has immediate and longer range missions. The

second-echelon has only an immediate mission and a direction of attack.

Types of Support

There are three methods of support by one unit for another. These are: (1)

attachment; (2) direct support; and (3) support.

Attachment

Attachment, or under command, is the closest form of support. The attached unit

comes under the direct command of the unit to which it is assigned and is

treated like an organic unit. The senior commander has full choice on how to

utilize this unit. When a unit is attached, its commander reports to the senior

commander on the situation and capabilities of the unit. The unit is moved

according to the orders of the senior commander. Sometimes (usually not in the

operations order itself but in the coordination instructions) the units are

listed telling when they will be detached and moved to other units. This is

especially true for the commitment of the second-echelon unit. At that time a

number of supporting units will be detached from a first-echelon unit and moved

into the second-echelon with the time and place of the attachment clearly

spelled out. As the second-echelon unit approaches the line of commitment it

receives its new attachments. When a unit is in defense and a counterattack is

planned, the coordination instructions will mention which units are to be

attached. A unit that is attached still receives its rear service support from

the parent unit, but the responsibility for supplies rests with the unit to

which it is attached.

An attached unit can include artillery, tanks, engineers, signal, chemical,

antitank, antiaircraft, etc. A division could have 4 or 5 or more artillery

battalions attached from army, while a regiment in the main attack will have 2

to 3 artillery battalions attached. The headquarters of a division or army

artillery regiment may also be attached to form a headquarters for the

regimental artillery group. The regimental chief of artillery is responsible

for all artillery fire in the regiment command therefore disqualifying him as a

commander for a regimental artillery group (RAG). The RAG is then commanded by

either of the battalion commanders or a headquarters brought in for the

purpose.

Attachment is terminated only by the higher commander who ordered it. There are

certain phase lines at which changes are usual. These include when units pass

to exploitation and pursuit and when first-echelon units revert to reserve or

second-echelon. During the opening phase of a meeting engagement, the advance

guard has attached artillery. When the engagement develops into an attack and

an artillery headquarters is established to control fire, this artillery

reverts to support. During a retreat the artillery is attached until a new

defensive line is established.

Direct Support

Direct support is usually established at a lower echelon than attachment. For

instance, when one or two tank companies are attached to a rifle battalion a

tank company or tank platoons can be placed in direct support of rifle

companies and not attached. That way the battalion commander retains control of

the tank missions. When a tank company is in direct support of a rifle company,

the main decision is made by the rifle company commander, with the tank company

commander supporting him. The tank company also receives its own missions,

which must be coordinated with the rifle company. The tank company may receive

changed missions at any time.

Support

Support is the least confined form and is used more for artillery units. For

instance, out of the regimental artillery group one battalion will be in

support of a first-echelon rifle battalion. The artillery battalion commander

receives his missions from the artillery group commander for fire direction.

The supported rifle battalion can request additional tasks and, if the missions

of the artillery permit it, they will support. Placing the artillery battalion

in support of a specific infantry or tank unit facilitates coordination because

the regimental artillery group cannot coordinate the fire support. The rifle

battalion can go directly to its supporting artillery battalion. The artillery

battalion in support usually sets up its command post close to the command post

of the supported unit. During the artillery preparatory fire the artillery

battalion is tied to the total plan with specific tasks. During this time the

infantry and tanks are moving forward. After the attack commences, the

supporting artillery is free to give more support on call. When an artillery

subunit is in support of a tank or infantry unit, the artillery commander

reports to the other commander on his capabilities, location, status, and his

missions from the artillery group.

During the attack there are three phases for artillery: (1) preparatory fire;

(2) supporting fire; and (3) accompanying fire. Most support for particular

rifle units comes in phase 2 and 3. During the second phase, until the regiment

accomplishes its immediate missions, the artillery does not usually have to

displace. When the attack moves into the enemy depth, beyond the range for

support, then the artillery will move by bounds and relocate to accompany the

infantry or tanks. Being in support means to provide adequate fire during the

development of a mission.

At the battalion level a battery of artillery may support one company. The

battery commander is then in direct communication with the company commander.

The artillery battery commander sets up his own observation post from which he

directs the battery fire.

In an advance guard situation the units of artillery or tanks will be attached

to infantry rather than in support. Also in pursuit and movement to contact or

whenever the infantry unit has an independent mission it is better to attach

the supporting units. For instance, when the infantry is an enveloping force in

the mountains or desert, the artillery will be attached.

Reserves

There are several reserves including the antitank reserve and the mobile

obstacle detachment. There are special reserves such as engineer, signal, and

chemical. The engineer reserves are used for employment in engineer roles, not

for use as infantry.

Combat Dynamics

The Soviet view is that combat is a process, a two-sided dynamic process, which

takes place in a given space and time period and with given inputs. The Soviet

commander's purpose is to control the output or resolution of the process in a

way favorable to himself. The process is a series of actions, reactions, and

counterreactions extending throughout the specified space over the period of

time. The time and space variables are themselves subject to control, as are

the Soviet input and actions. In addition, the Soviet planner and commander

believe it is necessary and possible also to control the inputs and actions of

the opponents, or at the very least to anticipate them and prepare accordingly.

Soviet planners have studied the history of combat actions, conducted

experimental exercises in field maneuvers, and developed a theory which links

the time and space parameters with the forces of the two sides engaged in

combat. The theory forms the basis for structuring the Soviet forces and

deploying them with missions corresponding to their capabilities to defeat the

enemy forces to be encountered in the defined action, and to generate a

momentum in their attack which will grow rather than diminish over time, as the

Soviet force moves deeper into the defender's area.

A unit has a certain capability based on the correlation of its power versus

the opponent. The initial mission is assigned to insure that the superiority of

the force enables it to accomplish the mission in a certain time period.

Analysis is made of the defender's dispositions and possible courses of action.

Basically there are two courses for the defender for the use of the reserve.

One is to hold in place and the other is to counterattack. If the counterattack

is to succeed, then it must be launched at a certain time and place in order to

be effective and must have a certain force available to overcome the attacker.

By careful analysis of the defender's situation the Soviet attacker can predict

the most probable time and place for the potential counterattack.

In the initial attack the battalion attacks the defending company in the

first-echelon of the defending battalion. For this it uses its two

first-echelon companies, which give it a 2 to 1 ratio over the defender. The

attacking battalion can overcome this defending company and move into the depth

of the defending battalion position. Now the defender must decide on committing

the second-echelon company. In order for it to restore the situation it must

attack before the first-echelon company is overrun, otherwise it is too late.

In general the Soviets do not believe a defending battalion can launch a

counterattack with this second-echelon company because there is not enough

time, the space is to small, and the force ratio is adverse to the defender.

The defender is better off keeping this company in position in defense. In any

case the attacking battalion uses its second-echelon company plus the remainder

of the two first-echelon companies to attack the defending second-echelon

company or battalion reserve.

Meanwhile, the adjacent first-echelon battalion of the attacking regiment is

attacking the other first-echelon company of the defending battalion. Thus,

when it also moves into the depth of the battalion defense it also confronts

the same second-echelon company being confronted by the other battalion. Thus

it is clear that the attacking battalions can overcome the defending battalion

and keep up the momentum of their attack to their initial mission depth.

At this time the defender can intervene with a counterattack by the

second-echelon battalion of the defending brigade. This is actually the first

real possibility for counterattack open to the defender. This counterattack

must be launched before the first-echelon defending battalion is overrun. This

counterattack is capable of slowing the momentum of the two attacking

battalions or of stopping one of them.

Therefore, the attacking regiment determines where this counterattack would

logically come and prepares to delay it, or stop it, or overcome it with its

own second-echelon battalion. The attacking regiment plans for the commitment

of its second-echelon battalion at the time and place that will carry the

momentum of the attack further into the defender's depth, to the line of the

subsequent mission of the regiment.

The division establishes its immediate mission at the line which the

first-echelon regiments are capable of attaining unaided. In order to increase

the momentum and achieve its long-range mission, the division plans to commit

its second-echelon regiment at about the time the first-echelon regiments

attain their subsequent mission (division immediate). The division also

recognizes that it is at about this time in the combat that it will most likely

have to contend with the counterattack of the defending division reserves.

The division mission is given on a daily basis. Thus its planning is done for a

day of combat at a time. In accordance with this concept the division daily

plan provides for the full day's actions of the division as it seeks to fulfill

its immediate and long-range missions on time. The division plan gives detailed

immediate and subsequent missions to the first-echelon regiments, which start

the day's fighting, and an immediate mission to the second-echelon regiment,

which is planned for commitment part way through the day. The first-echelon

regimental plans give detailed immediate and subsequent missions for their

first-echelon battalions and an immediate mission to their second-echelon

battalions. All these plans are developed for specified time and space

dimensions within which the Soviets believe they can predict the outcome of the

combat. It should be noted, for example, that the second-echelon regiment does

not give missions to its battalions until later in the day, when the exact

dimensions of its task are more clear. Nor does the initial combat order

contain the missions which the first-echelon battalions of the first-echelon

regiments will receive later in the day, when they have accomplished their part

in the regimental initial attack.

The important concept to understand from this is that, while the division

creates a daily plan and has in this sense a daily decision and planning cycle

geared to produce a new plan for each day, it also is engaged in continuous

decision making and planning throughout the day as it constantly responds to

the requirements of the unfolding battle.

In the Soviet view the division is the highest tactical formation. Its daily

activities are in the realm of tactics. The army and front are

operational formations whose activities constitute the essence of operational

art. Operations of the army are planned and conducted on a larger scale of time

and space than those of the division, but in theory they are structured in a

similar manner. The first-echelon army is given an immediate and a long-range

mission for its first operation, which corresponds to the front

initial (immediate) mission. The missions the first-echelon army will perform

in its second operation, during the achievement of the front further

mission are not given. The second-echelon army is given an immediate mission

corresponding to its line of commitment planned for two to three days into the

front offensive, but not a subsequent mission.

Thus the scale of combat governs the time and space dimensions of the unit's

battle and the duration of its plan. A battalion battle normally lasts for two

to three hours, for which time its probable actions can be forecast. Its plan

accords with this. The regiment battle lasts for five to six hours, during

which its actions can be forecast and planned for. The division battle lasts

for a single day, as does its plan. Armies fight operations lasting 5-7 days

and fronts conduct operations lasting up to 15 days. (The following

tables summarize Soviet norms for missions and expected counterattacks).

|

|

| |

RELATIONSHIP OF MISSIONS

IN TIME AND SPACE

|

| UNIT |

WIDTH OF ZONE -

KM |

IMMEDIATE

MISSION |

SUBSEQUENT

MISSION |

| DEPTH KM |

TIME HR |

DEPTH KM |

TIME HR |

| BATTALION |

1.5 - 2 |

4 - 5 |

2 - 3 |

8 - 10 |

4 - 5 |

| REGIMENT |

5 - 10 |

8 - 10 |

4 - 5 |

16 - 20 |

6 - 8 |

| DIVISION |

15 - 20 |

16 - 20 |

6 - 8 |

40 - 60 |

DAILY (long range) |

Figure 5 Relation of missions in time and space

|

|

| |

NORMS FOR EXPECTED

COUNTERATTACKS

|

| DEFENDING UNIT |

LOCATION OF COUNTERATTACK IN FIRST

LINE |

TIME |

| BATTALION |

COMPANY - 1 KM |

1 HR |

| BRIGADE |

BATTALION - 2 - 3 KM |

3 HRS |

| DIVISION |

BRIGADE - 6 - 7 KM |

4-5 HRS |

| CORPS |

DIVISION - 10 - 15 KM |

7-8 HRS |

Figure 6 Counterattacks

|

|

| |

Correlation of Forces and Means

Frontages

The calculated breakthrough frontages for units are 1 km for battalion, 2 km

for regiment, 4 km for division, and 8-10 km for army. The breakthrough sectors

for a front may be twenty-seven to thirty kilometers. The breakthrough

for a front is not the sum of the breakthrough sectors for

first-echelon divisions, since there will be many divisions not operating on

the front's main or secondary axis, which nevertheless have their own

breakthrough sectors.

Norms

Soviet planners have norms for expected rates of advance in various conditions

and for comparing forces in the correlation of forces and means calculations.

Under usual conditions they expect the rate of advance to be 25-30 km the first

day of an offensive for the main axis in a standard defense situation and 60-70

km per day on subsequent days. If the defense is well fortified then the rate

of advance the first day would be 15-20 km and subsequent days 30-50 km. In

order to achieve this they would require a two to three times superiority over

the defender. If the ratio (correlation) of forces and means were only between

1 to 1 and 2 to 1, they would plan conservatively and expect a slower rate of

advance. If the ratio were over 3 to 1, then they might hope for a 40 km

advance on the first day. Since the rate of advance depends on the type of

defense, they might expect a higher rate of advance even at two to one against

a weak or hasty defense. The nationality and training of the forces involved

also is a factor which can be considered in the estimate. The Soviet planner

thinks about the actual situation confronting him in terms of pluses and

minuses from the standard norm for standard conditions and judges accordingly.

If too many minuses show up he becomes very careful and conservative. He would

begin to think about committing the reserves earlier or if the situation

appeared extra favorable, he would think about committing the reserves later.

Soviet planners discuss the qualitative aspect of forces and means when

considering the correlation calculation. By this they mean that correlations

should only be considered between items of like quality. They do not compare

different weapons systems having radically different quality or lump together

items of different quality.

The norms for density of artillery relate to caliber and compare equivalent

weapons. For tanks they calculate the probability of kill for comparable tanks

such as M-60 versus T-55 or how equivalent is a T-62 to a Chieftain etc. When

comparing units they take into consideration the size. If there is a great

difference in size, they multiply by a number that will bring some equivalence

into the equation. For instance they do not compare a company of 100 men with

one of 160 but multiply by a factor to bring the two into relative equality.

Calculations

The extent to which the Soviet commander and staff rely on numerical

calculations to give them a sense of impending failure is often exaggerated in

Western literature. It is true that Soviet officers perform far more numerical

calculations than Western officers would, but they are not rigidly tied to

these. They do not give up just because the numbers appear adverse. Initiative

is emphasized in the Soviet sense, which means determination to overcome

difficulties. Figures do not override judgment or cause collapse of morale. If

the correlation suggests that superiority cannot be gained on a given axis at a

given future time and place, then that is a signal to correct the plan for the

situation. The commander should consider moving in a different direction, using

a different organization or some other method to regain the balance/correlation

calculation that he desires. Even if the correlation of forces indices are not

favorable, the commander must come up with some plan to stop the enemy

counterattacks. While this plan may have to be approved at a higher level, the

Soviets believe that officers who plan in the face of difficulty or do

something even if it turns out wrong later are preferable to those who do not

try to identify any alternatives.

Definition of "Forces and Means" in "Correlation of

Forces and Means"

The term, "forces", refers to the human element in organized combat

units of organized fighting structures of combined arms. Non-combat units,

e.g., engineers, etc., are not counted in the correlation of forces. In

calculations of the correlations at the tactical level, the unit two steps

lower than the command doing the assessment is taken as the unit to be

measured. For instance a division would calculate the correlation of forces of

battalions. At the operational level and strategic level divisions are the

subject of the correlation of forces analysis. All other elements being

correlated are "means". These are the hardware or firepower

generating elements such as numbers of artillery pieces, launchers, nuclear

warheads, aircraft, tanks, etc. (Tables for recording correlation data are

given in chapter 5).

The correlation of forces alone does not show the means. Both are important. To

consider, for instance, only battalions without reference to the type of

weapons they are armed with is to obscure very significant differences. In

particular such specific means as air defense weapons and antitank weapons are

very important. But for the others, specific coefficients are attached to each

type of weapon. These coefficients are based on detailed studies and modeling

of the weapons' characteristics and their contribution to the battlefield, in

particular, the probability of hit ascribed to the weapon.

Correlations between weapon types at the tactical level are based on the

relative number of the weapon required to kill an opposing weapon. For instance

in the attack it may take three antitank weapons of ATGM type to equal one

tank, while in the defense one antitank cannon may equal three tanks.

Thus the correlation of means may be seen as a test to insure that the force

has a proper balance of weapons. The individual means are identified and shown

separately in the correlation tables to demonstrate the existence of this

balance. The correlation shows that the units possess the necessary ratio of

means in each critical category to achieve their mission.

Some examples of tactical level correlations of means are the following: A

RPG-7 has a value of .3 versus a tank. This means that three RPG-7s can stop a

tank and that three will be lost in exchange for a tank. An antitank gun is

equatable to two tanks in position. An ATGM is equal to one tank in the defense

or three tanks that are on the offense.

In this manner standard scores (SUA) for each weapon type and model of weapon

have been developed, normalized on a basic model, such as the T-72 tank. The

various models of tank in opposing forces can be compared. When it comes to

normalizing the different kinds of weapons, such as artillery and tanks, into

one numerical score system Soviet writers express reservations. The issue is

the validity of factors for comensurability. They insist as a minimum, that

such unified scores must not obscure the fact that one weapon can substitute

for another only to a limited degree. Such scores are taken as averages for the

weapons when employed in the context of an all-arms formation. However, in real

combat each battle is a unique and widely differing situation in which average

conditions may not exist.

In addition to using the scores aggregated by class of weapon, Soviet

theoreticians aggregate them for units as a whole to develop composite unit

scores. However, these scores are based on much more than a mere addition of

all the weapons scores. In fact the research data base for the score ascribed

to a U. S. division comprises a small book.

The correlations are determined in tanks, artillery, etc. and at higher levels

by divisions. The infantry and tanks are the main measures. At the tactical

level they count every weapon and use weapon correlation factors to make

comparisons. There are multipliers for each weapon and unit. Weapons in the

open have one coefficient and if dug in another. At a higher level, the

coefficient is applied to division sized units. Some of the coefficients for

quality used in the 1970s are shown in the following table.

|

|

| |

National Unit Coefficient

The following table shows standard Soviet coefficients for comparing NATO

divisions to the Soviet motorized rifle division taken as 1.0.

Figure 7 National unit coefficients

|

|

| |

The most detailed plans that use the exact weapons counts with their

coefficients are done at division level. Lower levels do not have time for such

calculations. These calculations are used when deciding on the location for

commitment of second-echelons and special units such as antitank reserves. When

calculating the ratios for periods later in the combat, previous losses are

considered. In planning the expected casualties are usually figured mostly as a

matter for rear service support questions including medical. The expected norms

vary with the echelon. Some representative estimated norms for casualties are

as follows:

An army in WWII took .1 to .8% losses per day. Now with nuclear weapons losses

will be 3.8 to 5.3% per day.

For nuclear, during the entire army operation losses will be 27 - 42%.

For conventional war losses will be 1.1 to 1.3 % per day.

For the entire operation losses will be 7.7 to 10.4%

Equipment losses in WWII were 8-9% per day, now for nuclear war losses will be

12-15% per day.

For the entire operation tank losses will be 50-80%, APC losses 30-40%, and

vehicles 40-60%.

Of the total losses in personnel the breakdown is as follows: nuclear

casualties 16-18%, conventional weapons 6-7%, chemical wpns 5-6%, biological

wpns 1.5-2%, illnesses 1.5-2%. 30% of the total casualties will be caused by

the initial nuclear strike.

General Purpose for Correlations

Correlations in general are used as a way of determining which side will have

the upper hand, broadly speaking, in the action being studied. (For nuclear

weapons it is much more important to preempt than to have a higher value in a

static correlation. One should accept a major gap in the time phasing of the

operational and strategic components of the initial strike in order to preempt.

Therefore nuclear correlations do not tell as much as conventional

correlations.)

After the correlation is made one can decide if one can accomplish the desired

level of destruction "simultaneously" - that is in a single blow. If

the correlation shows a deficiency, then one must do it

"successively", - that is in a series of sequential strikes. This

method would require careful prioritizing of targets. (One of the most noted

characteristics of the nuclear strike is that it gives the potential for

successful achievement of strategic aims by simultaneous destruction. A

successful NATO nuclear strike is expected to destroy up to 30% of WP forces.)

However, conventional combat will almost certainly require successive attacks.

This is the phenomena which forces the commander to divide the non-nuclear

operation into phases and to focus much attention on proper coordination of the

use of forces and means.

Scope of a Correlation

When correlations are performed, they are done on several variants. This

typically includes correlations for the entire width and depth of the combat

zone, for the entire width and to the depth of the immediate mission,

separately on each axis, and for the time at which major changes in the

situation are expected to occur such as during enemy counterattacks and during

the commitment of the friendly second-echelon. This requires that the commander

not only make a static correlation of the forces as they are believed to exist

prior to the battle, but also that he calculate a dynamic correlation of the

forces that are forecast to exist at the future stages during the battle. The

method for doing this is discussed below. (See correlations tables in Chapter

Five).

As mentioned above, the purpose for calculating the correlation of forces

existing between the friendly and enemy forces in the given situation is to use

this relationship as a tool in making the decision and planning combat. The

calculated correlations are therefore compared with "norms" for

correlations considered necessary in various situations to accomplish various

kinds of combat missions. An element of judgment enters into the commander's

comparison of the actual correlation with the correlations prescribed in the

norms. Some Soviet writers indicate that more analysis and modeling of

historical combat is needed in order to develop more refined norms that would

show the correlation required in various situations or, in reverse, the

capabilities that a given correlation might confer on the attacker.

In any event the Soviet commander knows that there is a definite relationship

between the correlation of forces and the scheme of maneuver and manner for

organization of the battle that will be appropriate in the given conditions. If

the particular scheme of maneuver is the critical factor and the given

correlation indicates that the forces are inadequate, then something must be

done to improve the correlation. If the correlation is fixed due to lack of

additional forces and means, then the commander must adjust his scheme of

maneuver to employ the forces in a manner appropriate to the situation. For

instance, having a very favorable force ratio would enable the attacker to

strike on multiple axes to split the defender into groups and attempt near

simultaneous destruction of all the groups, while simultaneously launching

forces into the exploitation to the full depth of the defense. With a smaller

advantage the attacker might employ only two major attack axes to conduct

converging blows to encircle as much of the defender as possible and then

conduct the further offensive as a subsequent operation. With little or no

superiority in force ratio the attacker would be limited to concentrating all

available forces in one spot in an effort to destroy the enemy piecemeal

(sequentially).

The correlation of forces is only one of the norms the commander uses as tools

during his estimate. Perhaps a more critical one is the norm for density of

artillery. (See discussion of artillery fire planning in Chapters 2 and 5).

The correlation of forces and norm for artillery per kilometer of breakthrough

frontage are applied strictly to the width of the attack zone, which does

include a zone on each side from which defending direct fire weapons may hit

the attacker. But they do not include forces further on the flanks. The

measures match the Soviet echelons against the defending forces to the depth of

the corresponding mission. The overall correlation of forces at higher levels

such as front just shows if an attack can be made. The detailed

correlations are done at lower levels for the widths of the attack sectors. The

correlation method shows the areas in which the enemy is strong and weak and is

used to help determine the form of the attack, such as penetration here or

envelopment there. The specific correlations determine the directions of the

main attack and what forces are needed to achieve the desired ratio.

Correlation of Air Defense

Air defense is a special category of combat, which requires a somewhat

different kind of correlation. For this the correlation is measured in terms of

the percentage of an enemy hypothetical mass strike which can be destroyed by

fire during that strike. Individual air defense weapons also have individual

kill probability numbers. The Strella 2m has a .3; the 57mm gun had a .25; the

ZSU 23-4 had .42. These numbers are based on field tests and experiments.

In a conventional war, air superiority for either side is critical. Without air

superiority then neither side can win. Soviet planners see that they cannot

move their second-echelon forces forward. Air superiority is also essential for

attaining air reconnaissance, rear service, etc. One can not operate in a

conventional war without air superiority. Therefore the correlation of forces

and means for air and air defense is especially vital.

Evaluation of Decision Variants

The central problem facing the commander when seeking to make a decision is

which of the seemingly infinite but actually limited number of possible methods

to employ to achieve the mission. By method we mean how to task organize and

deploy the forces and means he has and what series of actions to order them to

employ. However this problem is complicated by an underlying pre-requisite

problem, namely the commander must first decide how (with what staff

organization and deployment of decision aids and series of assessment actions)

he will go about solving his combat problem.

We do not know the decision process Epaminondes used when he developed the

revolutionary idea of massing his Theban forces 50 ranks deep on the left of

his line instead of the traditional 12 ranks deep on the right of the line, but

it is clear that he faced a very simple set of issues compared to those facing

the modern commander.

To a great extent this underlying issue has been solved for the Soviet

commander by development of a highly organized troop control system and

procedure. Indeed the purpose of this handbook is to describe what this system

is and how the Soviet officer uses it to simplify his decision making problems.

In a sense therefore, the entire focus of the organization and processes

described here is one of helping the commander make this single (but

continuously shifting) decision on how to place and employ his forces and

means. (As Clauzwitz said, "In war everything is simple, but the simple is

actually very complex".

In addition to providing a well practiced decision system, the Soviet army also

provides each commander with much assistance in the form of relatively rigid

boundary conditions and guidelines in the form of the higher commander's

concept of the operation and directives giving clear terrain limits,

objectives, timing, location for the main effort, and other requirements. The

task remaining for the lower commander then is reduced and limited to how best

to maximize the power and effect of his given forces and means to achieve the

required goals. The number of reasonable alternate solutions is limited,

usually three or four at most and the differences between these alternatives is

very small. To illustrate this we can focus on the division level.

Calculation of Probability of Mission Success

Determining the liklihood of mission success is one of the most crucial issues

facing the commander. During his decision and planning process the commander

must not only forcast the liklihood of success of one concept of battle, but

also do this using a method which will allow for objective comparisons of the

liklihood of success between different possible variants of the plan. Soviet

military theorists and writers have proposed various methods for making this

forcast. The first issue is to decide on objective criteria for just what

result of combat will be labled "success". Three separate criteria

have been proposed, which can be evaluated individually. The overall

probability of achieving one, two or all three of these measures can then be

calculated using simple mathematical rules for aggregating probabilities.

The first criteria of success is achievement of the mission, which is generally

stated in terms of seizing a specified line or area within a specified time

limit. This is considered a vital criterion, so that a low probability in this

measure is automatically considered a fatal flaw, no matter how high the

probabilities for the other criteria.

But simply seizing the required line on time is not a sufficient indicator,

because this might be accomplished at such cost that the forces could no longer

advance, or might even be extremely vulnerable to counter-attack. Therefor two

other measures are added.

To maintain a high capability to continue the attack the attacker must have

losses of less than 40% of his force, the defender must have suffered losses

sufficient to destroy his ersistance. This is considered to be greater than 50%

of his strength, and attacker must continue to have supplies. Or even if the

attacker's loss is 40%, then, if the attacker maintains superiority and remains

in good condition overall, and the enemy has lost defense capability, the

attack may continue. The commander can forcast the losses which might occur on

both sides and put this algorithm into the calculation of criteria of

effectiveness. The idea is to campare not merely the mathematical expectancy of

the size of the loss on each side, but rather the losses calculated in the

specific situation at a defined confidence level. The system for comparing

candidate variants must answer four questions:

What is the probability of accomplishing the combat mission; that is reaching a

specified line or area in the depth of the enemy position by a certain time?

What is the probability that losses can be inflicted on the enemy of no less

than ordered, usually (50%)?

What level of confidence can be assured that at the moment the troops reach

this line they will retain their capability to continue the offensive, that is

have losses less than specified (40%)?

What is the probability of accomplising a partial or entire success?

To determine these answers in the course of comparing and selecting variants of

the plan the commander may construct a simple matrix as shown. He then can

apply the formula for calculating the aggregate probability for each variant

and select from among them. This problem and the calculations going into it are

discussed in more detail in Chapter Six. In that chapter are the nomobrams used

for determining the relationships between probabilities of achieving required

rates of advance and casualties and correlations of forces.

The probability of seizing the required line=G.

The probability of inflicting required losses on enemy=Y.

The probability of having less than maximum friendly losses=B.